lines and clouds (1)

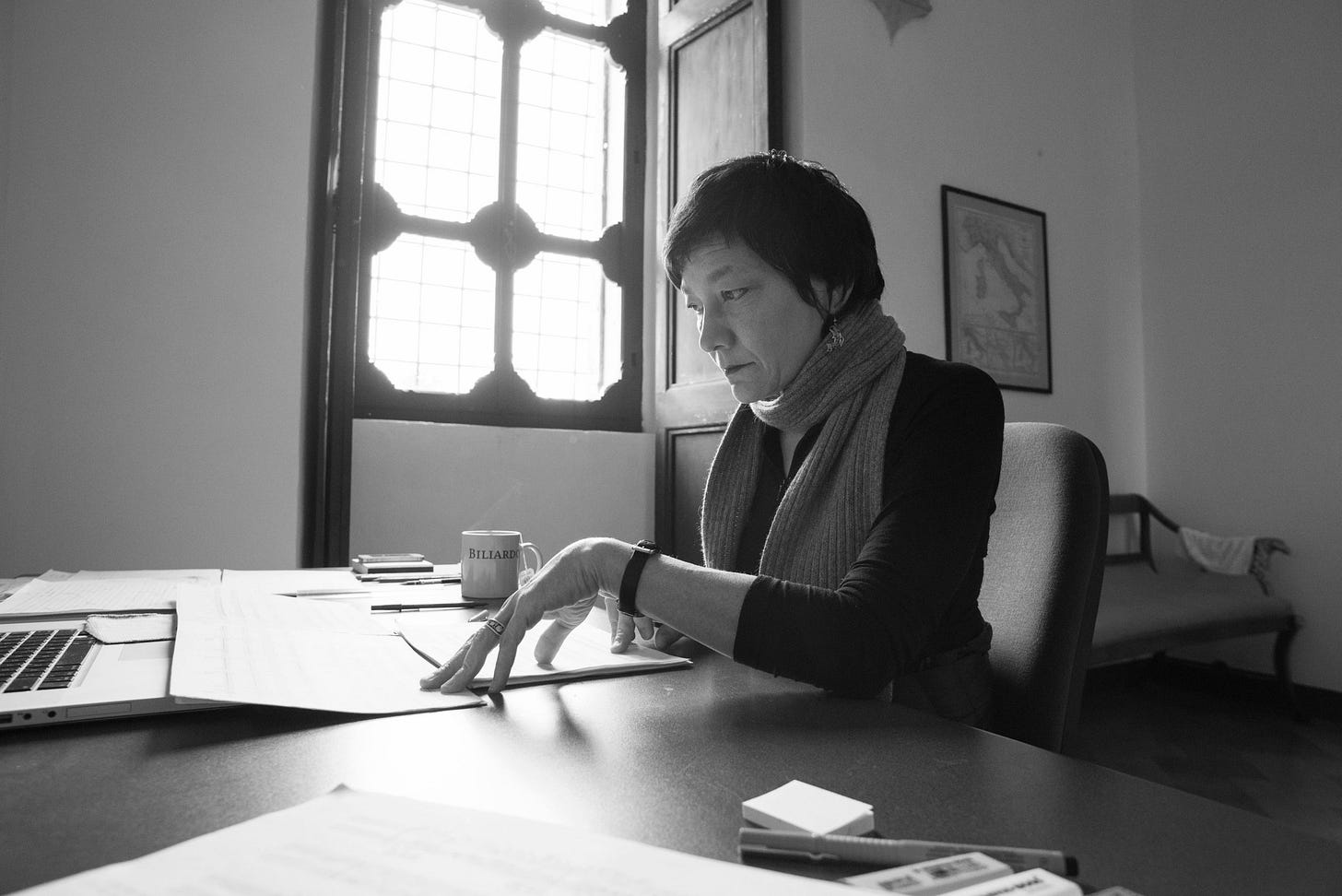

Chiyoko Szlavnics

Hallo liebe/r Leser/in,

Ich bin züruck, after une petite, well-deserved, pause. In a few words: I’ve let myself… live. Is that decadent? self-indulgent? luxurious? Yes. And no. Did I have the choice? 100% nein. First, it was hard to know what/how to write about after my last deep dive into Cenk’s brilliant works, and I was pretty be-wild-ered since September. So I thought a break a break would let me return as a disciplined, dedicated, resilient and dyslexic hermit—until the end of times. But here I am [ still dyslexic but ] more in touch with a kind of lightness, malleable openness and yeah, undisciplined joy. I’ve just been (re)learning basic decency. Not grandiosity, not self-effacement: just basic decency. Truth is a) the finding out of decency is nothing short but phenomenal;1 b) it’s not as easy as it seems for us, little humans.

In essence, all I’m trying to say is that I’m ready to enter my Sagittarius birthday season with a renewed sense of trust, bébé. I’m in Berlin, waking up to colorful people and gray skies, spending most of the day quietly alone, but greeted at night by warm words and hugs from friends, and falling asleep in an apartment where the reliability of the heating system is inversely proportional to the number of cigarettes smoked by the previous tenant (windows closed) and/or to the number of home-(tree)less bugs constantly streaming in (windows open). And I, Lucie Nerdy, frankly feel on top of my game. I’m onto somethin’ big. somethin’ decent.

And you know what always helps with growing as decent human beings? Listening to music and delving deep with the eyes & ears of a new born. Achso, bring your teddybear, put on your pacifier, your bib, and, most importantly, your widest, wildest smile, because, today, dear reader, we’ll listen & reflect on the work of a dear friend: Chiyoko Szlavnics. In this first post, I’ll introduce you to her and her Gradients of Details and we’ll celebrate a more recent work/release of hers in the next post.

Need I say: this post will follow the usual 4000 words format, including deeply felt ideas around music, composition and listening [mostly, not mines], and irrelevant comments & footnotes [strictly mines].

Chiyoko

Canadian, Berlin-based, composer, graphic artist, saxophone player, translater, singer (+ impeccable cook ), Chiyoko Szlavnics (CA/DE) has one of the most interesting, notable trajectories among contemporary composers today.

Online, one reads that Chiyoko was born in Toronto to a mother from Vancouver—the granddaughter of Japanese immigrants—and to a father of Serbian-Hungarian descent. Both parents were artists, both marked by the weight of WWII. Somewhere on a beautiful corner of the internet, there’s also the story of her visits to her maternal grandfather: a nature lover, fisherman, and devoted mushroom hunter who took her to see the salmon run on the north shore, teaching her about the salmon’s life cycle as she absorbed the stories, driftwood, stones, kelp, and tiny crabs. In many ways, she was already entering her lifelong contemplation of nature’s regenerative power.

All of this—family history, early encounters with nature, layered heritage, lives in Chiyoko’s work, alongside a high sensitivity, an analytical mind, and a contemplative stance toward sound. Perhaps the presence of mixed heritage opened the way to her unusually broad artistic affinities: Western classical practice, improvisation, Gagaku, just-intonation cosmologies, and, very importantly, Dhrupad.2 In her case, “mixture” is not a stylistic, anecdotical gesture but an ethic, an art of living and composing.

In the early 1990s, while still living in Toronto and after finishing university in 1989, Chiyoko looked into Gagaku Music, a probable entrance door to Chiyoko’s fascination for with slowly bending pitch, combination tones. The latter was later fed by her studies of Dhrupad in the Dagar tradition, which she began in 2017, first with Marianne Svašek, then the incredible Pandit Uday Bhawalkar.

Another major influence was her time with James Tenney (1993–1998). They discussed composition, musical parameters, Helmholtz, acoustics, and of course just intonation. Like for many, Tenney seems to have been an empowering teacher: someone who encouraged her to experiment and build systems rooted in her own intuition and curiosity. [digression: i still haven’t heard stories about Jim being a “complicated” or “difficult” person/teacher. +the genuine affection i witness in his students whenever they mention his name feels like confirmation that he was an extraordinary mentor—one who opens your eyes and lets you see an (your) endless field of possibilities.] [ = this is lineage ]

Chiyoko moved to Berlin in 1998, continuing her saxophone and improvisational practice while surrounded by musicians such as Ute Wassermann, Ulrich Krieger, Marc Sabat, Robin Hayward, and the broader improvisation scene (Andrea Neumann, Axel Dörner, Polwechsel, and others). Around her were also festivals featuring works by Alvin Lucier, Klaus Lang, Peter Ablinger, and the Zeitkratzer ensemble. She began encountering Wandelweiser-adjacent circles around 2003, a period that also marked the start of her drawing and painting practices. Later, after moving to a new apartment in 2008–09 with thinner walls and neighbors prone to vocalizing their complains when she played saxophone, her music grew quieter. But no less colourful.

Here is one may see Chiyoko today: through her humility; her methodical, precise, yet non-dogmatic approach; her quiet audacity and playfulness. She also possesses a remarkably astute way of integrating her music education while maintaining a healthy distance from the rigidities of academism—a stance we could all learn from:

As a legacy of my university training, I still open books of theory and try to understand what it is about that theoretical knowledge which academics want to establish so firmly. […] However, when one experiments and makes discoveries oneself, the phenomenal world feels so much more alive than if you are limited to an academic theory. There’s something so inspiring about that direct experience. What I’m always striving for in my work is that something—that spark which you can’t see beforehand, but which is quite magical when it occurs.”

Brief introduction to her general line of work

Chiyoko’s work lives at the threshold between abstracting the phenomenal world and engaging with it directly/ fiercely. Her compositions resist categorization—they are neither “conceptual works,” nor technical “tuning studies,” nor “figurative” or depictions. Instead, the tension in her music emerges from the meeting point between a poetic reading of psychoacoustic phenomena and a deeply cosmological orientation.

relation to the phenomenal world: shapes and tuning

Chiyoko’s work with just intonation is uniquely experimental, guided by “lines” that trace the unfolding of sound forms, bringing out the subtle experience of rationally tuned harmonies and melodies. If I may don my pompous sorcerer’s apprentice hat, the mastery of Chiyoko’s craft and the richness of her pieces lie in how the listener perceives a spectrum of superimposed Gestalts and cognitive streams—a continuous oscillation between:

Macro form ↔ macro listening: cognition of emerging, ever-changing shapes, “energy forms”, passing like clouds—what Marc Sabat describes as “temporally disjunct forces across huge distances”.

Ultra precise tuning / micro intervals ↔ micro listening: the psychoacoustic cognition of beating patterns. As Chiyoko beautifully puts it, “beating in music […] moves me, like sunlight dancing on water.”3

This oscillation between macro-forms and micro-phenomena, structure and untamed vitality, is where Chiyoko’s mastery lies: a refined craft that makes listening a fundamentally open and dynamic process.

relation to drawing lines: not-knowing

Without revealing too much of what follows, it’s worth noting that for the past ±20 years,4 Chiyoko has often used line drawings as a point of departure for her work and translated into microtonal scores.

From this methodical yet intuitive practice emerges an epistemology: composing while embracing (+ for the very sake of) not-knowing [relatable].

This way of composing is not “indeterminacy” in the Cagean sense, but a way of composing that remains open to what the process itself reveals. In other words, composition becomes a form of inquiry, where not-knowing is a condition for emergence rather than a lack of direction, allowing Chiyoko to be “surprised” and “blown away” by her own music. Therefore, Chiyoko’s lines are never rigid, mathematical, or strictly representational. The drawings reject both a) a simplistic logic of one-to-one correspondence between visuals and sound, b) a “free interpretation” expected of musicians in other graphic scores.

In fact, Chiyoko considers “it as my task, as composer, to interpret the drawings musically, to decide amid all the possibilities what notes and chords will be played, to notate and orchestrate that.”5 & as, we will soon see it, the way Chiyoko musically translates her drawings is hugely impressive: it unfolds outside the constraints of harmonic–syntactic tradition while remaining precise. And in Chiyoko’s music, such a practice introduces a choreographic and spatial dimension to both composition and listening, which become acts of spatial orientation, re-orientation and/or disorientation.

relation to time: slowed-down-ness

Chiyoko’s contemplative approach to music-making (and life) along with her interest for acoustic beating, results in slow pieces with quasi-still sections. This slowness invites the listener to fall ‘into’ sound, its ever so subtle, constant shifts with heightened attention. This approach to slowness is radically distinct from “deep listening” practices like Pauline Oliveros’. Chiyoko’s music never comes with a verbalized methodology or explicit instructions for how to listen. Instead, the music itself carries as a kind of non-verbal (I dare say: telepathic) invitation for the listener to meet a most inner, impersonal vastness. [= can’t be put into words, u c what i mean ]

relation to timbre: spectral transparencies

As part of her idiosyncratic approach to working with just intonation, Chiyoko’s practice is also informed by her expert understanding of orchestration: the physical properties of acoustic instruments and/or sine waves, how they sound together, how timbres and spectra interact, and how JI can emphasize or generate “harmonic fusion” between them. This combined attention to timbre (almost spectral in character) and tuning has a consistently stunning, emotional effect in her music.

relation to performance: human

Although Chiyoko’s music involves a high degree of abstraction and precision, it remains, in her own words, “a human activity”. In parallel to her abstract methodologies, Chiyoko writes with specific performers in mind. And there is nothing mechanical about her compositions or their performance: “Sounds are not anonymous; human spirits are involved in producing them.” Amen.

And, we, as listeners, are allowed to be human spirits. My experience of Chiyoko’s piece often feels like absorbing multiple layers of sound, zooming in and out as I listen, and ultimately moving beyond the analytical or cognitive altogether—into a state of heartfelt wonder, and of wondering. That, to me, is the mark of the music I love most; &maybe the highest relief or gift music can offer.

Voilà, l’ami·e. We’re halfway through this post, so, before (finally) delving into Chiyoko’s Gradients of Detail, I virtually invite you to take a lil break, a lil tea, a lil walk a lil (tini) cigi—and then come back. [ do come back ]

Gradients of Detail (2005-6)

From 2005–2006, Gradients of Detail hasn’t aged a day. This was the first piece I heard by Chiyoko, and the one I tried to write about during my bachelor’s studies, i.e. a century ago.6 It’s time to revisit it today. The recording was released in 2013 on World Edition, and we’ll use this video as our reference. Viel Spaß, & feel free to take notes and train your listening along with me.

(just listening)

Alright, some first rough listening impressions of this bombastic piece:

It is radical in its primary focus on tones, dry approach to timbre (no extended techniques, no vibrato, allowing beatings to surface transparently), and overall steady/uniform dynamics, without any traditional climax. That being said, with its plateaux (sustained chords), shifts (straight glissandi) and silences, the music has a sense of direction. Sounds start ‘from somewhere and going somewhere’, emerging from silence with intensity and assertiveness, but without accent.

the quartet moves in and dropping out of unison, in and out of harmonic fusion (those “pockets of light”). Most of the time, the quartet sounds like a single voice: always aligned, always moving together through dense, shimmering textures. Because of the closeness of the tones and the complexity of beating patterns and harmonic fusion, it is often difficult/irrelevant to distinguish “who does what.” But occasionally, one instrument emerges from these dense textures, sounding against the other three (for instance). The music is also interspersed with quieter, more enigmatic sections in which some instruments appear more “isolated” and exposed.

quick bird view on the score

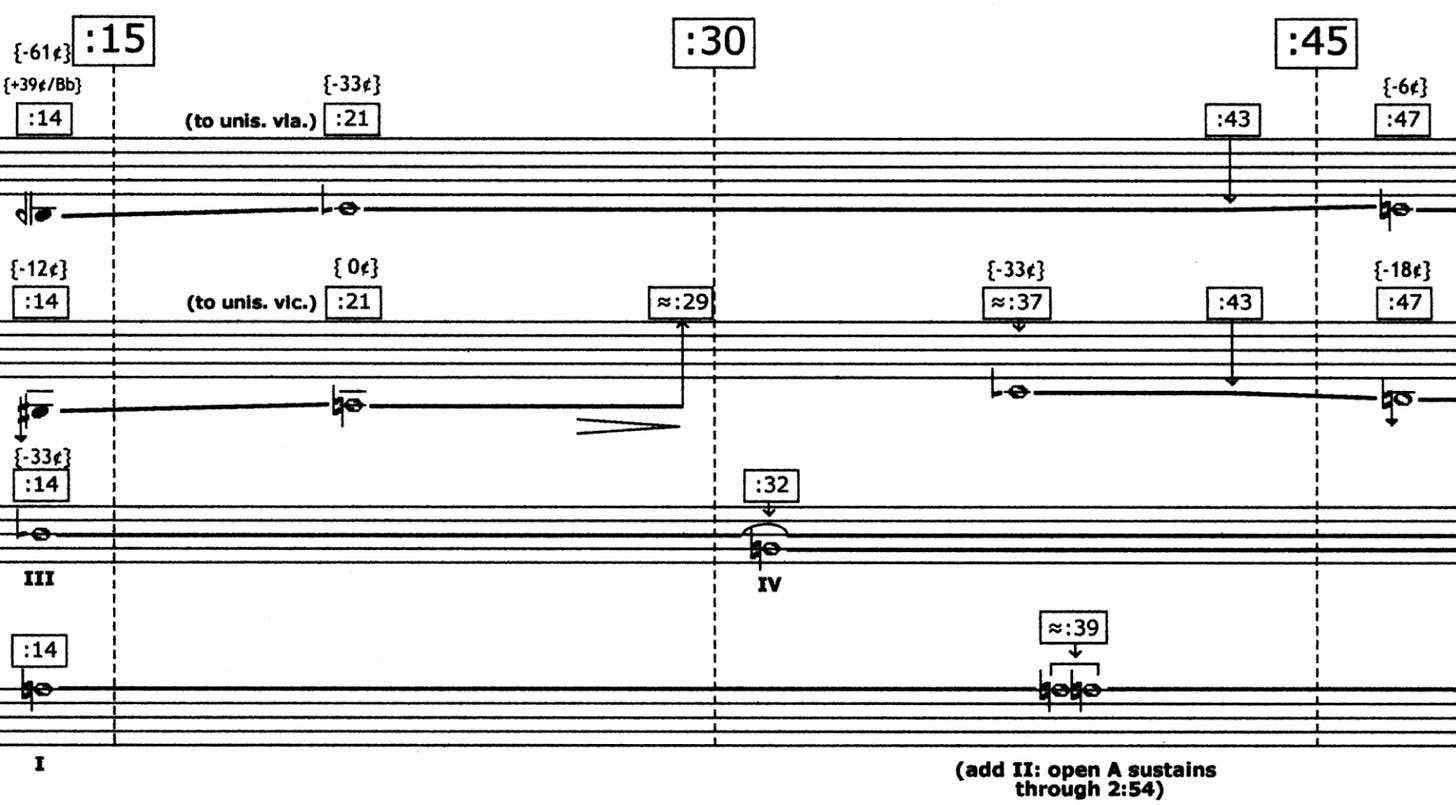

Without delving into its main, tonal material, here is what can be noticed in the score:

opening instructions, including the sharp and beautiful line: “expressiveness should be avoided — the form of the material is the expression”. boom.

Written parameters of:

durations, in seconds and bars consisting of blocks of 0’15”, 1’00” per staff;

steady, uniform dynamics of mf on all the voices (except two pppp on cello)

articulations: mostly absent, except for the following mention, Chiyoko’s style: “sustains should have a clear articulation at the beginning, but not emphasized”. We also find individual and collective, relatively short decrescendo throughout the piece (= Chiyoko’s attention is mainly focused on the way sound ends on a given voice); and a few, intentional, individuated pizz on the viola and violin II parts.

rare occurrences of string indications of harmonics or normal strings

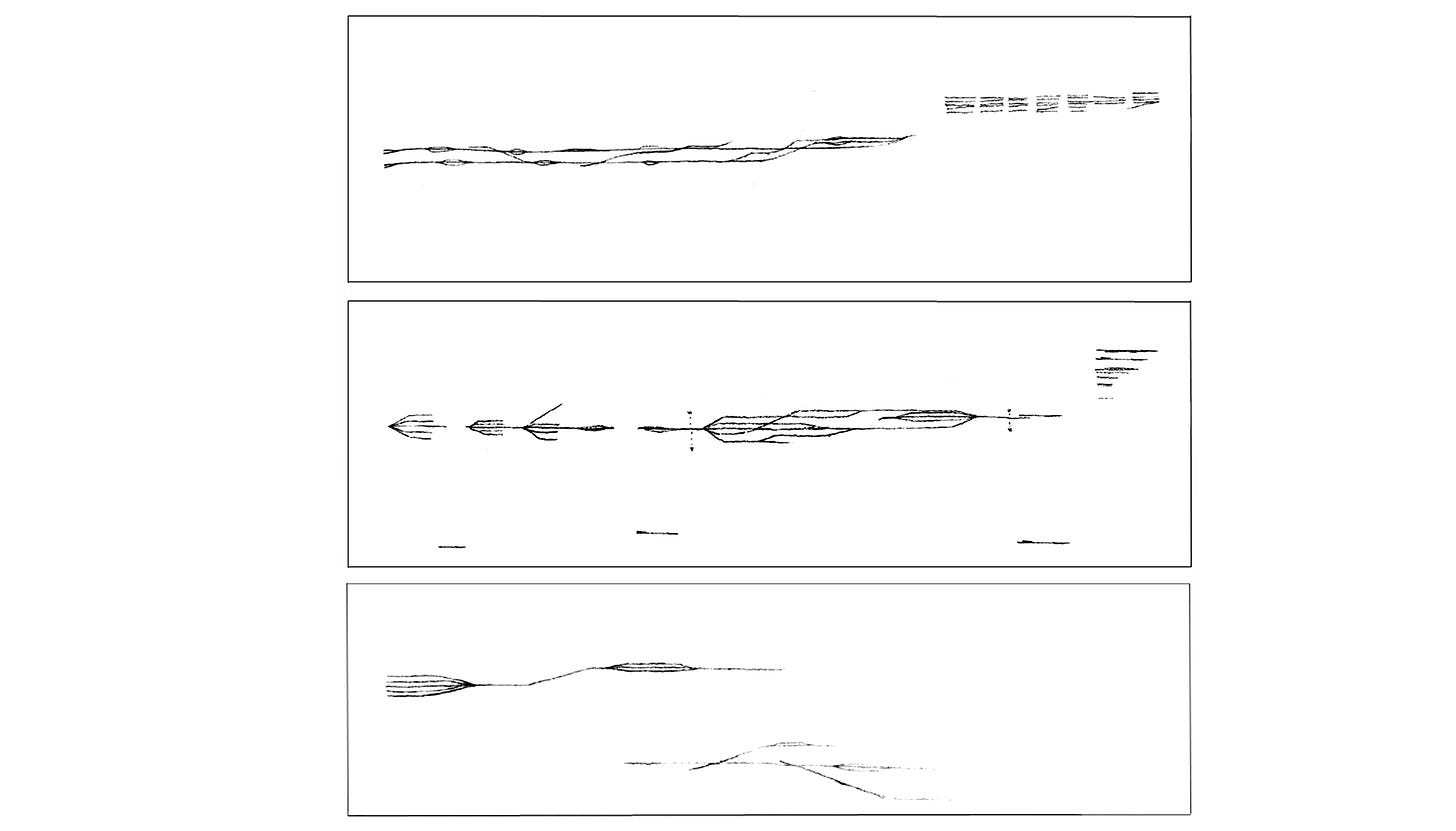

Gradients of Detail’s drawings

The drawings can be read as a chronological sequence: left to right, with silences suggested by the spaces between blocks of lines, and the vertical axis corresponding to pitch height. They reflect Chiyoko’s orchestration intelligence, since they are conceived in direct relation to the intended instrumentation of the piece. May sounds basic, but it’s not. Most often we find 4 lines—sometimes up to ±6-8, indicating the distribution of 1 string/tone per instrument and potential double stops. We see the voices merging into and diverging out of unison, while generally remaining in the mid-register (again consistent with a string quartet). Except at the very end of the piece, the lines tend to move upward, with a recurring lower, thinner line in the low register in the second drawing. Note that the lines are generally firm, except at the ends of sections where the upper blocks of lines loosen, and at the end of the piece, where all lines appear thinner, more fragile. [also: these drawings are beautiful as artworks ]

composing: interpretation/scaling the drawings into sustained, rationally tuned intervals

Gradients of Detail employs economical yet rigorous means of translating drawing into sound. The proportional mapping of the drawings—horizontally into duration, vertically into microtonal intervallic ratios—operates almost as a kind of analog wave shaping, where the contour of the line directly informs the evolution of harmonic and temporal structures. This mapping is not ‘sonification’ in an algorithmic sense, but nonetheless a precise, numerically-oriented transduction of spatial relations into tonal ones. Following Tenney’s and other JI lineages, Szlavnics uses “ratios as a network of interrelated pitches connected to each other through direct […] or indirect mathematical relationships”. More peculiarities of Gradients of Detail harmonic space:

Although they are superimposed and/or alternate throughout the piece, the denominators of the ratios= the “roots” (or what I call “tonal centers”) are fixed: A, B (more rarely) C, D, E (more rarely), G. Chronologically, the piece mostly revolves around C/ G/ D as tonal centres at the beginning; and ratios based on A tend to be more present towards its last two minutes.

From this clear, simple “pentatonic” basis, Chiyoko proceeds to a branching out of ratios in harmonic space, in a way that is complex and very clever:

Within each 15’00” bar, we find very close intervals with usually rather high nominators (mostly above 7). Sometimes, the root of the ratio remains the same and neighboring nominators are introduced sequentially on one individual part, but more often than not, the roots change and are mixed together both sequentially and across the different parts of the piece.

Let’s make sense of all that by briefly listen and look at score of the the first 45 seconds of the piece:

We encounter the following tones: 14/13/12:D and 16/15:A. In case this helps, here is a scheme with ratios:

vln1 : 13:D (B-61c) → 14:D (C-33c) (// vla) → 1:C (-6c) vln2 : 15:A (G# -12c) → 1:A (0c) ( // vlc) → (silence) → 14:D (C-33c) vla : 14:D (C-33c) [ → 14:D ] → 1:A vlc : 1:A [ → 1:A ] [ → 1:A doubled ]

Root-wise, the first violin revolves around intervals built from D before moving to C; the second violin begins with intervals from A and D; the viola starts on root D and then shifts to A; and the cello remains anchored on A. This interweaving process produces voices that move in and out of unison, while also ensuring tunability across the instruments and allowing for a wide variety of tones. It is a beautifully ingenious way of “travelling” through harmonic space, also in consideration with each instrument’s range and tunability (particularly when double stops are involved).

Now, in the piece as a whole, we may encounter numerators anywhere between 4 and 22. I was initially tempted to do a statistical analysis of when more complex ratios appear, as I have with other pieces by Tenney, Barlow,7 and others. More interesting would have been the analysis of the translation between the ratios of the drawings, and the ratios of the intervals in the score. But the truth is: there are no external “rules” that explain why Chiyoko’s initial drawing was translated into these specific ratios, or why they unfold as they do throughout the piece, beyond the drawing itself and Chiyoko’s artfulness. This mysterious mapping is everything—and I love it so much. We must approach these aspects of the piece with reverence and respect, for they are not meant to be analyzed or explained; we, dear reader, are not meant to “know.” There is no need to know.

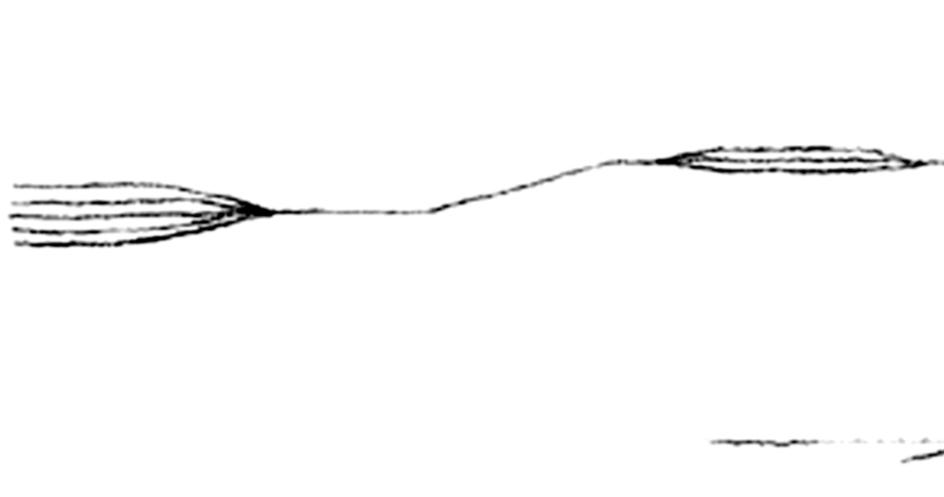

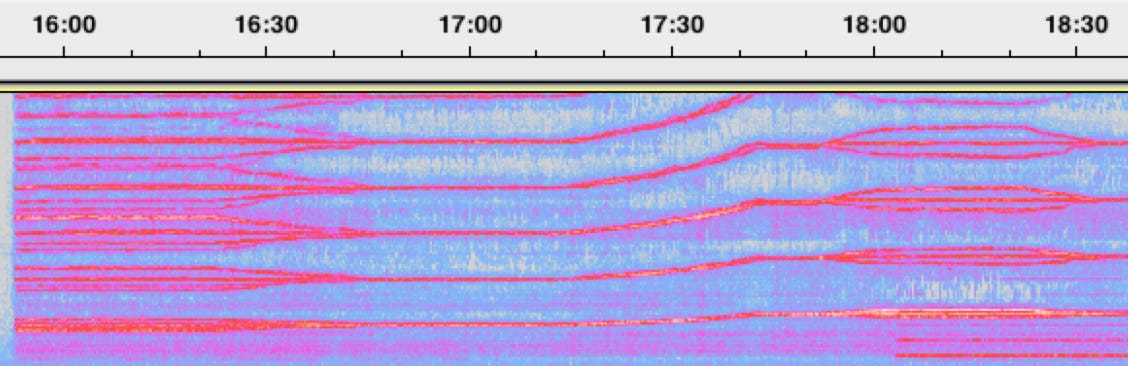

drawing and spectral analysis (16’00”- 18:30”)

Just for fun: let’s see how precise the translation is from: drawing, to sounding in the recording, to spectral analysis. [ and this, dear reader, will be proof of what composition can be like: the genius of composing, the creativity, precision, endless devotion and rewriting of perspectives of a single “idea”, until its realization is complete. enjoy ]

drawing

From this drawing, here is what we can expect in the music: 5 distinct pitches and equidistant/evenly spaced, sustained for a while, joining together at the same speed to one single pitch, holding that unison for a while, before moving as one single voice upwards, sustaining that pitch for a while, and then separating into 4 different voices: 3 upper ones (pitches close to each together) and one lower voice way bellow.

listening to the excerpt

For logistic reasons, I won’t include excerpts of the score but here is what I can say (and what we can all mostly hear in the recording):

16’00”: Beginning on a chord built over 5 pitches based on B and E, with a double stop on Vl1, and one pitch per instrument otherwise. The 5 initial pitches are: F#+6c, E+2c, E-55c, a D#-10c and an A-29c [not exactly equidistant in harmonic space. unfortunately, i don’t have the time or resources to get into this whole topic of intervallic distances in the piece, and how that differs with the perception of equidistance (or not) when listening to the tones together ] [ but if there is an invitation from you, i might proceed ]

16’30”: unison of the 4 voices on F#, all moving together to E at 17’00'“

the cello drops its sound at 17’15” ; the 3 others continue to their ascension from 17’23” up to G# until 17’53” and sustain it until 18’00.

at 18’15”, a lower A appears on the cello (corresponding to the the lower line in the drawing) and the 3 other parts start to separate from each other to different tones.

Let’s see now go full circle and compare the initial drawing with a spectral analysis.

[ prepare your astonishment ]

spectral analysis

Do I need to say more? Nein. Regardless of the ideas, genres, aesthetics etc, very few people can claim to come full circle—from their initial visions to the completed piece. This= the precision of the proportions of intervals and durations, the delicacy of the orchestration, and how it all sounds, is nothing short of astounding. But while Gradients of Detail’s spectral visualization comes incredibly close to the original drawings, the latter do not represent sounds one to one, and that remains true. To me, the music remains forever impossible to fully “picture” or grasp, resulting in a fundamentally disorienting listening experience. Super fascinating.

Voilà, dear reader. That’s my finishing line [= i’m out of jokes]. I’ll go enjoy Berlin’s last falling golden leaves, & see you in a few weeks for episode 2 — we’ll get cloudy

Lucie

[ i can’t get over this experience of going out for dinner with a friend on a sunday night, without any reason but the sheer banality of spending the time together, 0-stake, 0-performance, sometimes 0-chat. nothing to understand, heal, solve, share, etc, but it’s all warm. woof. i can’t get over that deep experience—those who know, know — you realize you never knew until you do, and that’s just woof ]

[ the last time we met, Chiyoko sang an Indian raga she was studying while accompanying herself on the tanpura. she was glowing, and the moment was unexpectedly overwhelming: the music moving through her, filling the room (and my mind) with those familiar flashes of light. it’s a memory that will stay with me forever. Chiyoko was vividly, herself. & self doesn’t fit in any box ]

[ fun fact: Chiyoko told me that since she couldn’t play saxophone freely at home in Berlin, she turned even more deeply to drawing as part of her compositional process ]

[ Peter Ablinger was the one who mentioned this piece and Chiyoko’s name to me during one 1:1 meeting in the Hague. a life-changing turning point. Peter was such a sweet man ]

[ in passing: is there interest in a post on Clarence Barlow?]

Such a wonderful piece, Lucie! Cool to learn more about what’s behind Chiyoko’s music. Those gradient drawings are a fascinating way to compose. Gave me some ideas around story craft. Her performance at Orgelpark did force me to slow down to become transported into the sonic landscape.

Lucie,

It is experimental, and I appreciate the math and aleatory nature of it, but to the untrained ear and mind, do you think it might resonate?