intersecting (2)

Cenk Ergün / Yekpare (2023)

Hallo dear reader,

Comment va? Wie was dein Sommer? Und hallo Zeptember, schön wie eh und je

Besides the most precious friends I’ve been lucky to meet lately, another cherished companion of mine these days is big old yoga buddy. I hadn’t spent proper time on the mat in years. And you know the saying: when a fairly lazy and soft body needs to yog, the mind has no choice but to give in. Not trying to convert anyone here, but come on, yoga is certainly one of the greatest, most profound, and refined innovations humans have developed. The experience it offers is continuously humbling. My body & mind are rusty AF but with the sweat, heavy breaths, & cracking joints (mmmm) come the deeper longing and slightly wider gaze on life, oneself and others. As I linger in wobbly warriors, attempting to balance upward with downward, one side with the other [= fully given up on understanding such concepts as left & right], inward with outward, flow with stabilization, the gross with the subtle, hesitations with openings, yoga has also become a lens through which to revisit, listen to, and read music. And maybe it’s no coincidence considering the piece we’re looking at today.

So, after introducing one of his piece, Celare, here is a second post on Cenk Ergün’s music, this time on his ± 40 minute long string quartet: Yekpare. As the piece hasn’t been officially released yet (but will be, in 2026), Cenk has generously shared a wealth of information and agreed that I can share short excerpts of the video recordings and the score. For these practical reasons, I won’t discuss the piece in depth/details this time, but I’m sure we’ll get somewhere, taking a macro perspective and explore the resonances the piece has within our current musical context. We’ll see how far I can go with this. Om. Inhale. Exhale. Chaturanga, updog, downdog—and you know, let’s all just stay in downdog for a moment, exploring the form, nice & steady, while reading this very short post. u’ve got this.

[ / little reminder of where we landed last time ]

Let me return to where we left off last time. My perspective was to explore the kind of mirroring between psychological processes on the one hand, and compositional logics on the other—how both can serve as conduits for cycles of individuation (whether of a person or a piece). More specifically, I became curious to consider Cenk’s work as a case study in the musical expression of post-migration subjectivity, where identity is never fully stable but constantly re-learned and re-heard. It is as if one revisits, again and again, the impossibility of grasping “identity,” while remaining open to the many facets that “identity” can take in music at a given moment.

In that sense, each musical or personal “reference” in Cenk’s music seems to have arrived in its own time—rather than being rushed into a ready-made synthesis of influences. His work gives space for these references to surface—whether in individual pieces, scores, or even across decades, as in the ten years separating Celare (2016) and Yekpare (2023). Both pieces are rich with references from diverse times, geographies, and traditions, yet they reveal radically different relationships to Turkish makam [note: makam = Turkish, maqam = Arabic]. Yekpare is, in this sense, more assertive; less polite, one might say [i like]. Through this renewed engagement with its source, Yekpare glows with an unapologetic musical confidence.

Alzzzzo. Let’s take a step back and cast a distant gaze on how the piece was built, how it came into being (without, as usual, any claim to exhaustivity). But first, let’s listen to excerpts performed by the unapologetic JACK Quartet.

Multilayered references to the pieces — what a piece is made of

As Cenk explained, Yekpare is the result of many musical and non musical influences. First, its title was inspired from Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar’s poem from 1933, Ne İçindeyim Zamanın [which was hanging for a year on Cenk’s wall while composing the piece ] and its first lines:

Neither am I inside time, nor entirely outside; / In the indivisible flow of a monolith [ yekpare ], vast moment.1

What’s particularly striking about this inspiration is that Tanpınar’s literature often grappled with the tension between Ottoman-Islamic cultural heritage and the modern, secularizing Turkish Republic. His writing frequently drew on Sufi imagery, blending traditional Islamic sensibilities with existential and aesthetic reflections—always as a cultural observer rather than a religious practitioner. This is especially telling in relation to Cenk’s approach to Yekpare, where he was listening not only to polyphonic chansons like Trebor’s Passerose de Beauté and Alice Coltrane’s radiant Kirtan: Turiya Sings, but also embracing what he himself calls “a secular infatuation with Sufi and Bektashi music [that made] its way into the piece through my non-Muslim but nevertheless spiritual lens.” At the same time, as Yekpare turned more deeply toward Turkish music, it emerged as an invitation for the listener to partake in a kind of secular ritual. During his exchanges with JACK, Cenk noted that Yekpare was shaped by pieces such as:

… or this Rast Naat composed by Mustafa Itri, totally an hymn in Turkey, especially during Ramadan + used as a prelude to almost all sufi music rituals.

[ btw: intentionally letting you listen to these pieces what you can rather than imposing any words on the experience of these pieces ]

flexibility with score, “form” & performance

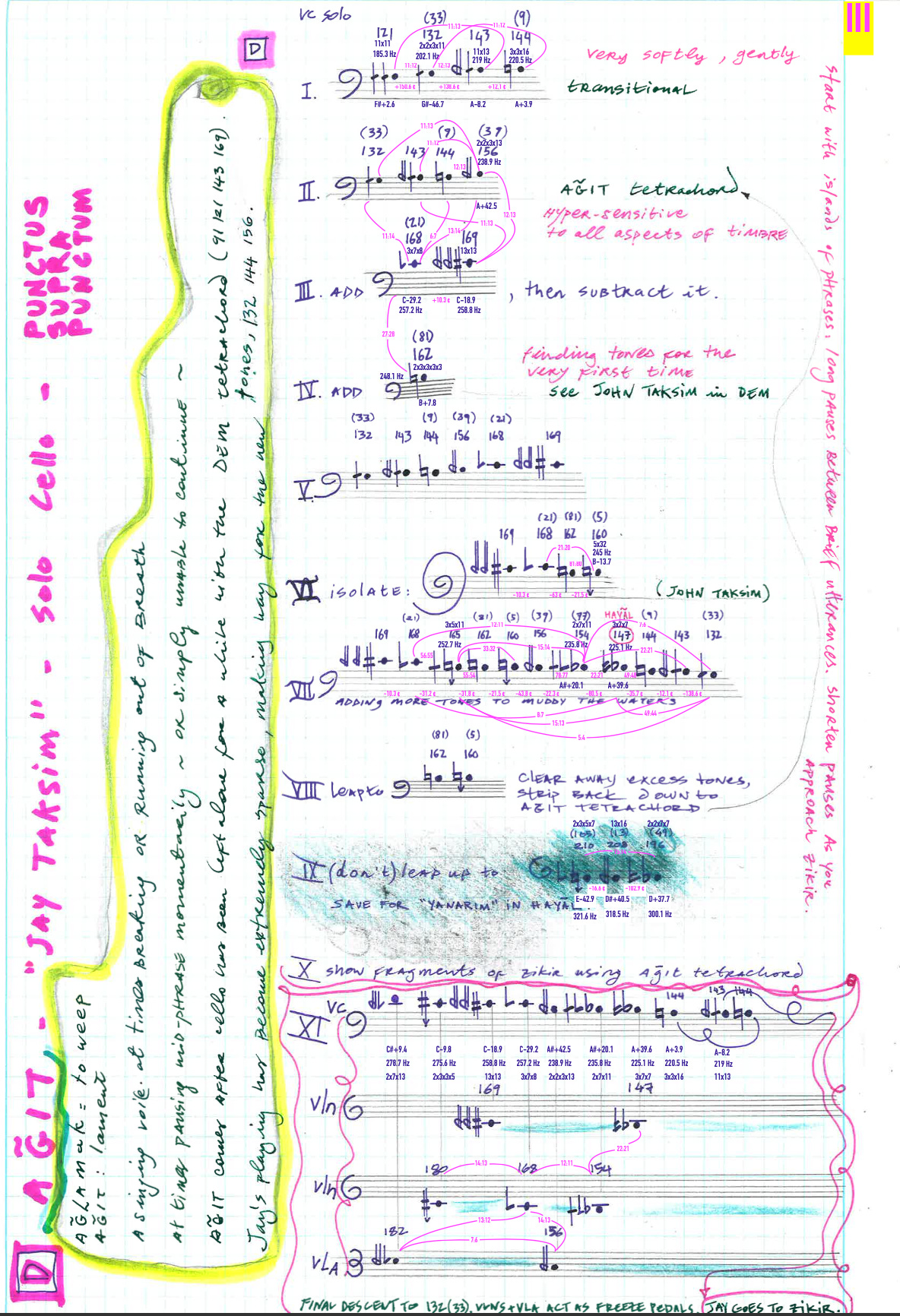

The scoring of Yekpare stands in stark contrast to the more traditionally notated Celare. Its pages are colorful, “messy” yet rigorous, playful, scratched, multilayered, multidirectional, at times echoeing to notational experiments of ars subtilior, at others just free and fun. Come on, look at thaaaaat:

The score of Yekpare shows a process of exchange with musicians, who were integral collaborators rather than external observers or mere “executors” of notation.

It reflects the work’s roots in aural and oral transmission, emphasizing rehearsal and performance over traditional scoring. This communicative orientation is evident in the pitch notation, which can be read through six different systems: Helmholtz notation, ratios, overtone numbers, ct deviations from ET, Hertz values, and intervallic relations. + i imagine, audio recordings of the tones.

Such an approach situates performance and collaboration as the space where time, i.e sound, is collectively experienced and discovered.2 = The temporality of the piece is thus shaped in rehearsal, with musicians, rather than being predetermined on the page. Strikingly, while this may appear fundamental, it is mega rare in “industrial” contemporary music contexts, where limited rehearsal time barely allows performers to inhabit or uncover the temporal dimension of a work. [ this is incredibly odd ]

. . . & central to this figuring-out-of-time process is Cenk’s return to his concept of the “wave”: “hearing and composing long tones in waves—that is, in swells: ppp < mp > ppp.” In Yekpare, this idea is extended across parameters such as register, instrumental and harmonic density, bow position, and more—sometimes prescribed, sometimes left as suggestions.

Another notable feature, and one entirely consistent with the work’s ethos, is that much of the piece is performed from memory. As Cenk observed: “With nothing to look at, I felt that the quartet listened better—and this is also a reference to traditional Turkish music, which is an oral tradition performed from memory. With no stands in the way, I think the quartet also formed a very intimate relationship with the audience.” aaaah, yes x100, couldn’t agree more. It’s a super great challenge for the musicians but gosh, that makes the music so lively in Yekpare.

tuning & blur between harmony and melody

Lettuce turn to the core of the piece: its remarkable tuning. Since Celare, and over nearly a decade of exploring rational intonation, Cenk eventually, as if “accidentally”, returned to makam sonorities through his encounter with the multiplication of primes up to 13. As he explains:

Multiplication with primes up to 13 gives me a great variety of tones that are beautifully related, and which can create endless chains of makam sonorities. So, multiplication with 2, 3, 7, 11, 12, 13 gives me numbers like 39, 49, 77, 91, 121, 132, 143, 144, 147, 169 – which I have found to be excellent at clearly expressing subtleties of makam intonation, at least enough to serve the purposes of my music… Now I can transcribe Turkish tunes using these numbers.

One of the major inspirations for Yekpare’s sonorities came from this recording already linked above, and specifically from the makams Huseyni and Ussak3. Both share A as their tonal basis and, from my mega basic understanding, their most refined shades lie in the subtle region between A natural and B natural. In Yekpare, the core tuning is based on G [G +0 c], or 256. The primary tones are as follows:

9 (leading) [A +3.9 c] — or 144, 3-limit (9)

10 (tonic) [B −13.7 c] — or 160, 5-limit

11 [C −48.7 c] — or 176, 11-limit

189 (almost 12) [D −25.3 c] — or 189, 3-limit (9)

27 (dominant) [E +6 c] — or 216, 3-limit (9)

121 [F +2.6 c] — or 242, 11-limit

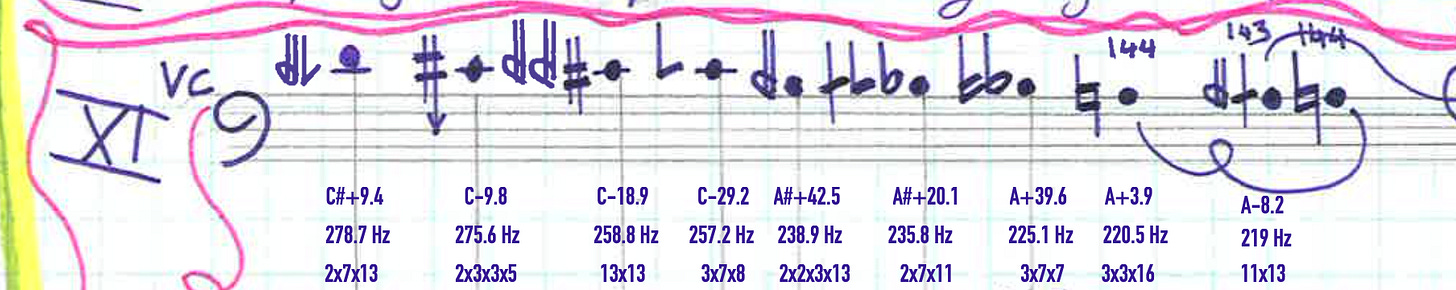

From these foundational tones arises a vast palette of additional colors or limits (−5, −7, and −13), creating a complex yet coherent tuning system always traceable back to the original makam scale of Yekpare. For example, the scale concluding the first section of the piece emphasizes the region around A and B, with no fewer than five distinct colors in that space:

Just this mini example reflects the broader compositional approach in Yekpare.

On the one hand, it achieves a saturation of colors by repeatedly multiplying ratios within their respective limits. Especially salient colors include:

13*13 — C −18.9 ct

11*11 — F# +2.6 ct

7*7*7 — C +6.5 ct

In addition, some tones function as what I might call “synthesized” or bridging colors between different limit poles. For instance, A# +42.5 ct results from G *2*7*11, while A −8.2 ct corresponds to G*11*13.

Very, very importantly, while the precise tuning of each tone is central to the piece [ the ct deviations are crézy ], Cenk approaches it with zero dogmatism or rigidity—the influences remain entirely open. As he described his palette of tones to JACK:

It’s our makam. Not Turkish, not Ottoman, not Sufi. Of course, that’s all in the DNA. But so is Feldman, Cage, Oliveros, Curran, Lucier, Tenney, Young, Alice Coltrane...

brief part by part analysis

Alright, I won’t spoil the piece for you, but here’s a sneak peek into its main sections. Originally, Cenk envisioned Yekpare as a “monolithic” series of chords, like those in its first and last sections, unfolding in slow waves. It feels to me that this approach soften or diffuse the references to makam while making them more accessible for those who are ready to hear them. Indeed, the slow, swelling, reductive material is particularly suited to reveal the subtlety and richness of the tuning variations beneath, allowing the listener to linger in it. However, when Cenk mapped his pitch collection onto a keyboard and played them rapidly and monophonically, a new dimension door opened. This faster material was incorporated into the middle of the piece, aligning perfectly with his approach [ which also sounds like a great slogan ]: “Melodizing harmony instead of harmonizing melody.”

Part 1 — Dem

Dem refers to a form of Sufi group meditation in which players drone on the lowest tone of the ney flute for extended periods. In Yekpare, Dem revolves around the tetrachord: 91 (C# +9.4 c), 121 (F# +2.6 c), 143 (A −8.2 c), and 169 (C −18.9 c). Microtonal differences in intonation are treated not as technical feats but as melodic, expressive, and, in my experience, simple “heart-opening” elements.

The section begins and ends with all 4 instruments, gradually introducing the tones of the piece interspersed with general pauses. It also features two Taksim: John Taksim, written for JACK’s violist, John, and Jay Taksim, written for Jay, the cellist [sweet]. The section results from the kinds of poetic, “merging-of-opposites” instructions that I love, and that I suspect many musicians find nightmarish: “Everything in waves / Waves in everything”, “one tone per instrument for relative stasis / 4 tones alternating on each instrument for relative flux”, “waves of single VS double stops. waves of sordino; waves of bow position, pressure speed, etc”.

Notably, ornamentation is absent, emphasizing a precise tonal exploration.

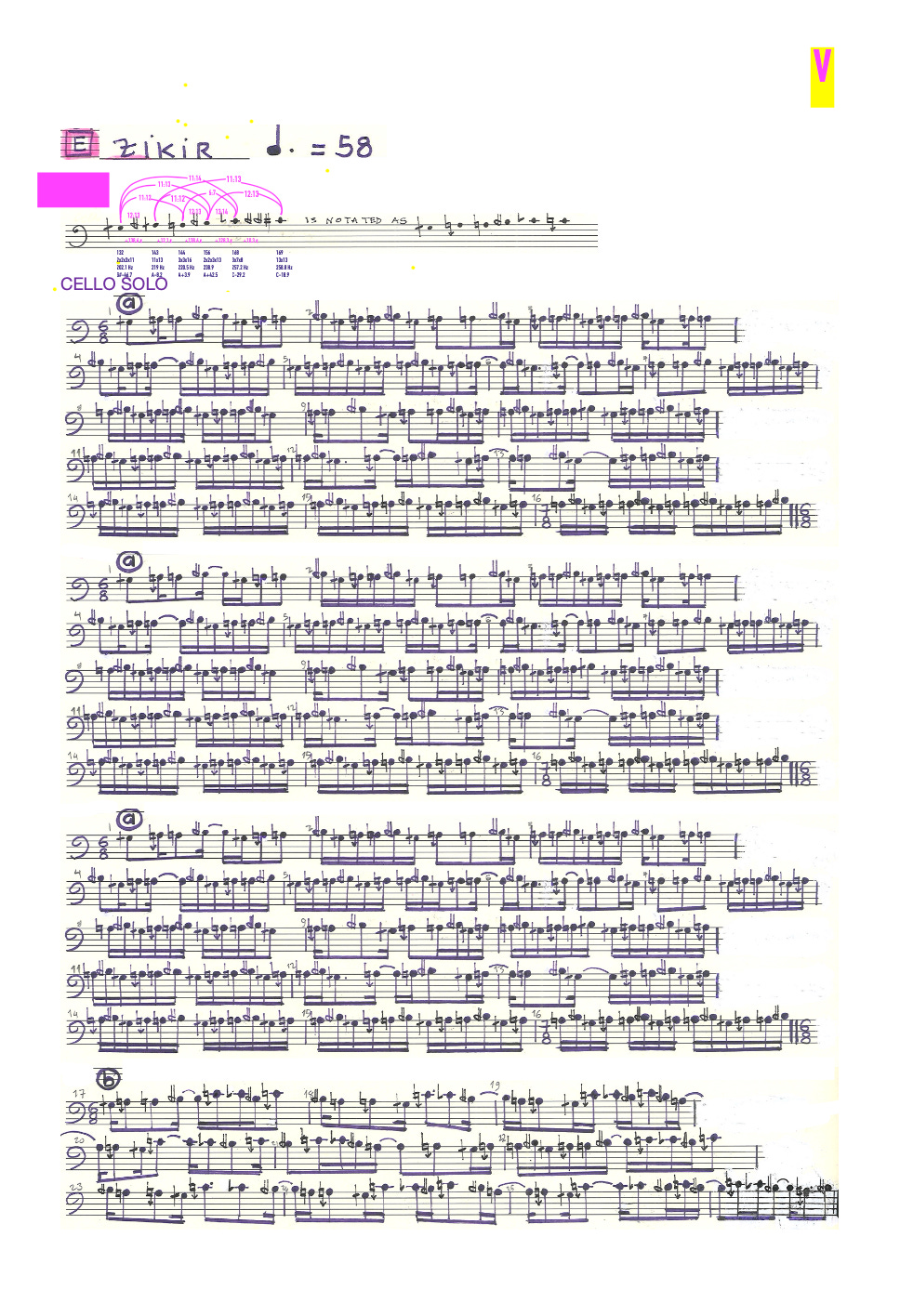

Part 2 — Zikir

This middle section, exhilarating and rhythmical, marks a clear and unexpected shift in the music. Borrowed from Sufi meditation practice, the term Zikir refers to a form of meditation that overlaps with Hindu and Buddhist mantra traditions, involving repetition of words, melodies, rhythms, breath, and movement. As you might guess, the aim of both the practice and this section is to alter consciousness: to reach a state of trance or ecstasy, followed by a sense of wellbeing, clarity of thought. Reflecting this, Cenk noted that he could imagine this section being repeated for an hour or longer, allowing the music to allowing the music to fully support listeners in reaching the highest of the highest realms. [ i’m not even joking: i did feel so shocked and high the first time i listened to this section — like ‘w o w’. ]

The fixed six-tone scale for this section is: 132 (G# −46 c), 143 (A −8.2 c), 144 (A +3.9 c), 156 (A +42.5 c), 168 (C −29.2 c), and 169 (C −18.9 c), again concentrating the material within the condensed pitch region around A and B.

The section is organized into 2 main recurring subsections:

(a) Primarily regular repetitions of a four-tone scale (excluding the Cs), with mostly ascending motions and occasional “syncopated” rhythms.

(b): Introduces the full six-tone scale (including the Cs) through downward more melodic motions, syncopated rhythmic cells. Super exhilarating.

(c): a slower melodic motif of the Zikir, made of waves of successively ascending and descending scales — very vocal, vibrant and slightly (= tastefully) ornamented, especially in its last/conclusive appearance.

Variations are introduced through instrumentation: cello solos, tutti played loco (at the notated pitch), and tutti with different transpositions (violins at 8va or 15ma, viola loco, cello at 8 basso). They also arise from textural shifts, ranging from bare tones to more and more bow pressure. Overall, this section gets louder, denser, brighter. The build-up is super effective, particularly through the dynamic curves (waves) from p to f in the repeating subsequences (a), giving the music more and more intensity until finding release in (b).

For both Cenk and JACK, Zikir is the most vulnerable and difficult section of the piece, and that is precisely what I find most compelling. Performing it requires a willingness to be open to / confront discomfort and the risk of sounding. . . “other”. This is striking because it remains rare to hear Western contemporary musicians engage with non-Western-inspired works, and equally rare to hear non-Western musicians approach contemporary compositions that draw from, but slightly deviate from, their traditional repertoires. In this light, any such uncomfortable bridges are in and of themselves interesting, valuable, and crucial, provided they are built on mutual respect and genuine curiosity. JACK did great.

Part 3 — Hayal

For Cenk, Hayal refers not only to the Arabic word meaning “image,” “mirage,” or “soul,” but also a genre of Hindustani music. “In the context of Yekpare, it is the state we arrive at after Zikir – clarity of mind… a clear perspective on the past and the way forward amid an aura of shapes… where all types of combinations of tones which before might have been out of place, can now come alive.” I must admit, this section gives me goosebumps so I won’t even attempt to analyze it too deeply. In a few words, it opens to wider pitch ranges, where harmonics and always light, subtle and retrained bass intersect, and denser, more focused mid-range swells and ascending scales, before concluding the piece with three descending trichords.

As Celare, Yekpare is tastefully composed, never climatic and yet. I hadn’t felt that much exhilaration and release in a piece in a long while. Alright cocos, that’s that: you’ll have to experience the rest yourself at the next performance of Yekpare. Let’s move on to some concluding thoughts. [ longer than expected ]

polarized listening VS permission to explore

As I was initially searching online for a program note about the piece, I came across a review [won’t link it] by an “educated” NYC writer/musician who attended the premiere of Yekpare. [sorry Cenk & all, i promise there is a point to be made ] The reviewer wrote Yekpare “was like Romanticism, but with all the wrong notes”. A constructive start.

There were quartertones and ultra-dissonances, but many times when they played together, an amorphous cloud of sound would resolve rather nicely into a fairly conventional cadence. There was also an attempt at melody […]. I think I even heard a fragment of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”… At times, it felt even rock’n roll, while one viola passage evoked a folk fiddler playing something that could have been out of Bartok.

Okay pause here: I don’t want to ridicule the writer [that was the very last review he wrote anyway]. But this paragraph, written in 2023 (!) illustrates a narrow, Eurocentric + conservative listening perspective—one lacking reference points outside the Western musical canon and thus ‘missing the whole point’ of the piece. Not only do such review not do justice to Yekpare and, I imagine, many more pieces of new music, but it also shows how stuck the reviewer is to engage with repertoires they are not familiar with.

Allow me dear reader, as usual, to take the risk to sound cliché. In the new music field or elsewhere, we all the capacity to cultivate this openness, curiosity and thirst for otherness — a deep appreciation for each other’s meandering paths in music and beyond, each other’s ways of writing, listening & being. And to me, this deep appreciation and acknowledgement of what is “other” provides the foundation for meaningful discussions about diversity and inclusivity in music. Without it, we risk boxing ourselves and others, defending our musical territories, traditions, and interests. & do we need that today Alfredo? noooOOoOOOoOOoooo. When this deep appreciation is present, however, something transformative can occur: what once seemed distant or alien can suddenly feel intimate, and what appeared “other” can become profoundly close.

+ While past encounters between Western and non-Western music were rare, these intersections are now unfolding more frequently and dynamically in the experimental music scene. Chosing to be mega optimistic: just as the presence of female and non-binary composers has grown, so too will the normalization of such ‘diverse’ pieces. Learning to ‘listen to’ this diversity is no longer optional; & nor is cultivating clarity about the contexts and lives we engage with. For instance, composing with makam/maqam scales today does not mean the same as it did 10, or even 2 years ago (yes). By zooming in and out, from the personal to the collective, and back, we eventually all face our biases, however uncomfortable that may be. Cultivating this honesty and openness in the ‘harmless’ music field [or on this harmful yoga mat] is always a meaningful, luminous place to begin.

Another side of the picture. My dear friend Nirantar has recently shared this post by Sami Abu Shumays about the Politics of Maqam Scales and the Decolonization of Music Studies. The article is rich, insightful, and thought-provoking/confronting in many ways and very, very much needed. Do read it. As Sami writes in his article:

The representation of scales as mathematically determined is inherently political, creating hierarchies of correctness and authority. When applied in a colonial situation, these assertions of authority through mathematics are a tool of White Supremacy, fostering exploitation and appropriation, denying agency to colonized peoples, and enabling cultural erasure, one of the accomplices to genocide.

Here is a response/contribution—take it for what it’s worth. For some of us, non 100% Western but Western-educated composers, approaching makam/maqam or other traditions through numbers is a way of ‘decolonizing’ ourselves. It is an attempt to reconnect with what our bodies resonate with, even if our minds have been Western-washed, sometimes by dysfunctional education systems. For Cenk, myself, and other mathematically inclined composers with non-Western roots, numbers have been a neutral entry point, a kind of playground, to rediscover our ‘colors’—in music, in scores, and sometimes even in our own skin. = structuring scales through numbers can serve goals close to those Sami Abu Shumays defends: reclaiming a heritage that felt lost, and resisting cultural erasure [ & more ], and carry a deep, deep reverence for these traditions though our unorthodox pieces. Here are Cenk’s own words, drawn from his exchanges with JACK and our brief email correspondence — a very sharp and balanced pespective imo:

20 years ago if you told me I would be thinking about makam, I would have laughed at you. Today I know it's an undeniable part of my musical DNA - even if I had no formal training in it. … makam was never been my goal with JI, but more and more, it has revealed itself as an arrival point I had been unconsciously traveling towards. I don’t advocate JI as a sufficient system to fully theorize about makam. But JI gives us access to these tones so we can play with them in our own terms.

Personally speaking, working with JI and Arab music has only widened what feels like an abyssal distance between the music I make and the music I love. It brought the heartbreaking question of why I was disconnected from Arab music in the first place. That distance, however, is what I am willing to work with and openly acknowledge [ + care for] in my music. No matter how ambiguous and amateurish the music may appear, at least I can keep learning to refine my stance and hold all its no-man’s-lands and contradictions. Cenk’s music has definitely given me the courage to embrace that standpoint even further.

Bon beeeeh voilà. I want to send my warmest, most positive thoughts and a HUGE THANK-YOU to Cenk for sharing and trusting this publication with his music. It has been such a treat and a amazing learning experience. I am deeply grateful and look forward to hearing your next works. And thank you all for reading & listening.

Simple love then, ni + ni -,

Lucie

multi ps: 1) EU-based friends: JACK will be perform Cenk’s music on 01.11.25 in Essen (DE)= be there or be square. 2) Berlin friends: i’ll be there some time during the fall, let’s be in touch. 3) URL friends: here is a very recently released piece by Cenk to wrap it all up

4) for you who are still reading, well you’re a sticky stalker at this point, so here is a sticky special gift: an excerpt from the story of the three non-existent princes.

Once upon a time in a city which did not exist, there were three princes who were brave and happy. Of them two were unborn and the third was not conceived. Unfortunately all their relatives died. The princes left their native city to go elsewhere. Very soon they fell into a swoon unable to bear the heat of the sun. Their feet were burnt by hot sand. The tips of grass pierced them. They reached the shade of three trees, of which two did not exist and the third was not even planted. After resting there for some time and eating the fruits of those trees, they proceeded further. They reached the banks of three rivers; of them two were dry and in the third there was no water. The princes had a refreshing bath and quenched their thirst in them. They then reached a huge city which was about to be built. Entereing it, they found three palaces of exceeding beauty. Of them two had not been built at all, and the third had no walls. They entered the palaces and found three golden plates; two of them had been broken into two and the third had been pulverised. They took hold o f the one which had been pulverised. They took ninety-nine minus one hundred grams of rice and cooked it. They then invited three holdy men to be their guests; of them two had no body and the third had no mouth. After these holy men had eaten the food, the three princes partook of the rest of the food cooked. They were greatly pleased. They thus lived in that city for a long time in peace and joy.

( may we all lavishly, non-existently proceed further )

The entire poem goes as follows:

Neither am I inside time, nor entirely outside; / In the indivisible flow of a monolith, vast moment.

Every shape, as if mesmerized by a strange dream color,/ Not even the feather flying in the wind is as light as me.

My head, an immense mill, grinding silence; / Inside me, a cloakless, hideless dervish who’s attained his desire;

The world is now an ivy with its roots in me, I am sensing, / Amid a blue, an all-blue light, I am floating.

in the words of Cenk: “One of those secrets for me is time. And I think sound provides many clues about time, and music can provide an infinite number of ways to experience the passage of time. Sometimes the musical experience can be ecstatic or spiritual, creating space for the listener to be in touch with these things that seem so fundamental.” https://15questions.net/interview/cenk-ergun-about-alternative-tuning-systems/page-1/