for kali

from the inside/out

Salut les nases,

Alors, au top ou gros flop? la pêche ou la fin des haricots? le bitter ou le sweet?

Or perhaps you’ve reached this enlightened gaze on things, where the bitter is the sweet, the pêche the haricots, the top the flop, the nase the wise?

I certainly haven’t, but you know, after a little pause, I’m back behind the keyboard, ready to spin my best words & tracks with a special sauce du jour. Indeed, allow me, dear reader-listener, to, fearlessly, for the first time here, and using Substack’s latest streaming technology, share a piece of mine called for kali.

Following the cool words heard from Chiyoko Szlavnics: sometimes it’s best not to reveal too much about the process behind a piece, and instead let the mystery remain intact. [a valuable lesson that may apply to many other areas of life we try to share with others. like cooking. dreaming. & other innocent activities]. So, while keeping the mystery whole, complete, alive, I’ll share just a few ongoing reflections on for kali.

for kali’s background

Initially, for kali was commissioned by Kali Ensemble and written for violin, cello, flute, clarinet, harmonium, piano and zither. The piece is inspired, from a distance, by the vast repertoire of Arab-Andalusī nūbat, in particular their modes and slower, semi-improvised sections. for kali is not an attempt to recreate this genre: it rather displays a kind of 'hollowness' — emptying the substance of these music traditions and eventually finding something that has everything but mostly nothing to do with them.

Why you may ask? It’s something I’ve been thinking about lately: studying the psychology of what I’m trying to do in my music as opposed to the concepts that might underpin it (which don’t feel especially relevant or appealing at this point in my work). To put it briefly: I’ve realized my music somehow addresses the loss of musical heritage and experience of marginality (real, or imagined, collective or individual). Theoretically, Arab-Andalusī nūbat would be part of my cultural heritage. But when contextualized in my actual genealogy & life, this heritage is almost entirely lost, gone, muted, inaccessible. [ mystery no.1 for some of you, but you may read a previous post of mine on Mustapha Skandrani & start to put some pieces of the puzzle together ]

Although I’ve only scratched the surface of how this loss has shaped my experience of life, it feels already crucial to clarify the posture I wish to develop in relation to it. For instance, I’m not interested in gazing at that loss with nostalgia nor an excessive, suspicious kind of pride and wonder. I’m also not drawn to claiming an ‘identity’ or a sense of belonging to a culture that was never truly transmitted to me. It just feels more aligned, honest and humbling to simply acknowledge the loss, in my music and life. Like a kind, heartful hello, there you are (or hello there, you are) — gently tiptoeing into waters that are at once familiar and unknown.

for kali, different versions

But back 2 the zikmu. Although the full ensemble version hasn’t come to life yet (fingers crossed it will someday), several other versions have emerged from the score so far: one for solo piano, one for two pianos, and one for piano and zitherJoel Gester Suárez and Nirantar Yakthumba.

Working with versions in my pieces has been a way to unpack their different facets, to get to ‘know’ and understand them more intimately through the prism of different musicianships, sensibilities, instrumentations, and configurations. This process often revolves around one recurring question in my work: how ‘bare/naked’ and reduced, or conversely, dense and extensive can the same material of one piece be presented? I believe for kali is a good illustration of this ongoing exploration.

for kali (solo / hollow)

Let me first introduce you to the solo version of for kali, performed by Nirantar.

DIY-recorded & performed by Nirantar Yakthumba in feb.25. as usual, feel free to:

Strictly focusing on the performance aspect of the recording, what I find most interesting about this version is its austere, polymorphic beauty — one that reveals the fluid, a-referential quality of the piece, or its ‘hollowness,’ waiting to be filled with references and projections from both the performer and listener. Personally, I hear at the beginning of the recording a restrained, careful, and ‘contemporary’ approach to sounding, with an emphasis on resonance. Midway through, I hear Niru transition into Arab-Andalusī touches, letting go of a careful ‘sounding’ and entering more expressive, wavering realms. Towards the end, it feels as though Nirantar grows curious and determined to lead the piece in a different direction, closer to classical music performance. This introduces a certain rigidity, if not quite literally a measure, which unveils some structural aspects of the piece, sometimes coming into friction with its fluid, melodic material. [ i dare say i hear in the last minutes of Nirantar’s performance (≠ the piece) something akin to Glenn Gould playing Bach. ]

for kali (duo / relational)

In the case of for kali, working with versions helped clarify the multiple sources of its ‘hollowness’. The latter is undoubtedly tied to the nature the piece’s melodic material, its equal simplicity and ambiguity/fragility. But this sense of ‘hollowness’ I was pursuing was reinforced by the openness of the piece in terms of performance and instrumentation. In a way, there is fundamentally no definitive answer to how for kali should sound. And it is worthy to try to make it sound, see how far one can go with it.

We worked several times with Joel and Nirantar with duos of piano(s) and/or zither(s). Now, I don’t have proper recordings of these rehearsals, but, perhaps because the piano is their primary instruments, the duo version played by Joel and Nirantar on 2 pianos was especially moving and effective for me. Here’s an excerpt below:

The piano duo version revealed two things. First, it brought to light for kali's core, i.e. its heterophonic potential, which, on the surface, is reminiscent of certain aspects of Arab-Andalusī music. In doing so, and at the risk of sounding nonsensical to some of you, I feel that the heterophonic texture in the duo version adds depth to for kali’s ‘hollowness.’ It’s difficult for me to articulate all of this with full clarity, but I sense that the more heterophonic for kali would be — that is, the denser its instrumentation (perhaps moving toward an Andalusian ensemble configuration) — the more the distance between the piece and traditional Arab-Andalusī nūbat would become obvious, abyssal. And perhaps this is where the loss of heritage would be most foregrounded as well.

A second, beautiful insight from the piano duo version lies in how it integrated the relationship between Nirantar and Joel as part of the music: their loving, interwoven playing, the way their respective musicianships and sensitivities subtly locked into each other (or didn’t), how they listened and got lost in each other’s sounds. Witnessing and fostering this kind of relational dynamic through music feels like an immense privilege: it is an offering and receiving of trust — a different kind of openness.

Here’s a little excerpt of the piano/ zither duo:

unmeasured notation + one melodic line (±= ‘hollowness’)

Keeping aside its algorithmic aspects [a-not-so interesting conceptual mystery no.2], here are the contours of my not-so-secret recipe in the piece: one single melodic line + unmeasured notation.

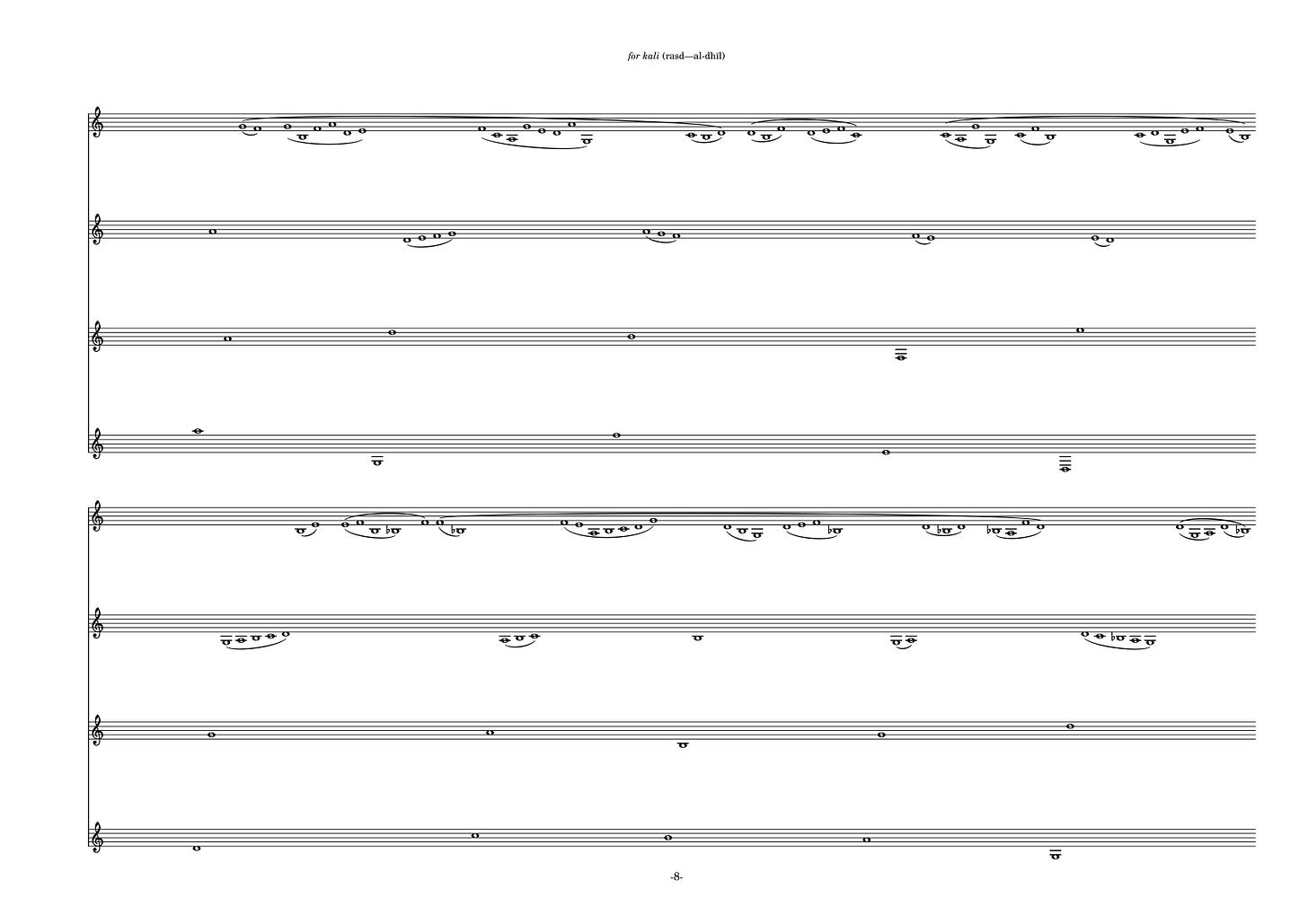

One initial challenge when composing the piece was working with restraints and limitations. More specifically, I aimed to stick to a single melodic line throughout the entire piece, ± keeping it all within the mid-pitch range and keeping harmony out of the picture — at least, on paper. Speaking of, here is one page of the score:

Like with any other pages, every note must be played by the performer, whether playing solo or in duo. As you may have noticed, none of the notes are vertically aligned = they are meant to be played sequentially. The score consists of 4 staves, each serving a specific function:

the first staff is the core, meandering, melodic line of the piece

the second staff features quick ascending/descending scales with an ornamental flavor to them

the third and fourth staves act as the skeleton of the piece, providing structural support to the melodic lines above [ not so interesting mystery no.3].

One reason for keeping the score at 4-staves score, despite the piece being monophonic, is to serve several purposes for the performer: a) to keep them fully engaged with the material, truly listening as they zigzag up and down the score;

b) to allow them, as they become immersed in the score, to eventually let go of the initial functions suggested for each staff; c) to encourage them to explore each line as having interchangeable functions — melodic, ornamental, and structural.

In short, as the performer grows more intimate with the piece, they may discover that the melodic line can become ornamental, that the second line can fully integrate with the first, or that the last two lines may become ornaments or part of the melody, and so on. Once again, this interchangeability contributes to the openness I’m interested in: taking the risk to get lost at times, taking the chance to find oneself at others.

‘hollowness’ / openness

Finding the right equilibrium when displaying the ‘hollowness’ / openness I am after takes time. This is something I also need to discuss with the performers IRL, to get to know them, how they play, to find their alignment in the piece. This is the actual mystery, one that I couldn’t even begin to articulate with words, even if I tried.

[ edit: you may find Nirantar’s impressions on working on the piece at the end of this post — his words are truly touching and perhaps he’s able to articulate what i can’t ]

In for kali and most of my pieces, I wish to retain openness, a lack of certainty, as a basic experience for both the performer and the listener. It’s not an easy position to maintain as a composer, and it’s certainly not an easy one for the musician to inhabit, nor for the listener to embrace. There’s a prevailing trend that asks composers to ‘own their material.’ I’ve never fully understood this. I’ve tried, time and again, to ‘own my material,’ but the more I do so, the more I realize that my approach to music is about not owning (or at least, owning the least possible) and not-knowing (or, at least, knowing the least possible).

I can’t help but relate that kind of proposition of musical openness as a way of being: how some of us prioritize living openly, decisively, yet lightly diffused, and developing the awareness that certainty is only an illusion. Don’t get me wrong, prioritizing a clear, conscious, defined direction and purpose is beautiful and necessary. But so is prioritizing the awareness that there is no ground, no real territory, no fixed identity. And music, in my view, can certainly help cultivate this awareness; it certainly did in my own experience as a listener.

The journey is still long before my music matures enough to offer these kinds of experiences to listeners, but this is the kind of road I’m on. Semi-patiently putting one small step after the next, while trying not to take the whole enterprise too seriously.

POUET.

That’s it for today, dear reader. I hope this made a bit of sense.

Thank you for tagging along this far — it means a lot.

for kali is available on SoundCloud [perhaps soon on Bandcamp if there’s interest?], where you can shower it with your virtual love.

( u kno, these small stuff do go straight to my heart )

warmly, springly,

Lucie

edit: Nirantar’s impressions on performing the piece:

the sort of indeterminacy that lucie brings into this work is quite bizarre, challenging, and confrontational at the same time. like a mirror, and unlike a mirror.

another mystery central to the work was lucie's skill for mental cues. wild horses, the movement of rivers. these cues brought me closer to the piece than even the score itself. but these images do not programme the music—they are not notes or instructions—and they change from one attempt to the next.

performing this piece feels less like interpreting and more like honing in on underlying secrets, which disappear from the mind as soon as the piece ends. but they leave a beautiful and uncanny impression nonetheless.

my new favourite work of yaoi