shade/gradient

an analysis of Catherine Lamb's piece

Ciao les beaux/belles gosses,

June okay so far? Starting to feel like summer? Already glittering/sun-bathing, summer-flirting, or pétanque-ing with Pépé Jean-Claude? or maybe sunbathing while flirting with Pépé Jean-Claude?

I’m happy to finally share this long-overdue post. Today, dear reader, we’re diving into a kind of musical monument: shade/gradient by Catherine Lamb. Go grab your fancy matcha and/or overly sweet chocolate bar from Jumbo, your stylish and/or greasy glasses, your soft, heavy blanket and/or your gross, smelly, stained hoodie — and without further ado, let’s fall into the multidimensionality of Cat’s music.

(very short) bio

Catherine Lamb [Cat pour les intimes] is an American composer based in Berlin, born in 1982. While Cat carries forward the legacy of James Tenney, her musical influences reach far beyond. At the heart of her work is the interaction of elemental tonal material—especially precisely tuned intervals played at subtle volumes, allowing acoustic phenomena like combination tones, phasing, and beating to emerge naturally. She’s been steadily planting the seeds of rational intonation in her music and collaborations, notably with the Berlin-based Harmonic Space Orchestra.

I think I can speak for many composers and musicians when I say we’re deeply grateful to Cat: for being a vital source of inspiration, and a generous teacher and sharer on her own terms. Her informal, open approach to mentorship echoes that of James Tenney, but is equally shaped by her second, deeply influential mentor: Mani Kaul. Since the early 2000s, his philosophy and approach to sound and art have guided Cat’s thinking, forming a bridge into concepts closely related to Dhrupad music. [ do watch the documentary below, filmed by Mani Kaul — c’est kdo, c’est gratis & an absolute beauty of a film ]

shade/ gradient

And speaking of Mani Kaul, shade/gradient is dedicated to him. Composed in 2012, the piece marks an important moment in Cat’s early, substantial, and systematic exploration of rational tuning, focused on her main instrument, the viola, along with voice and electronics. Whether you’re familiar with the piece or hearing it for the first time, let’s listen (or re-listen) and remember just how radically intimate, minimal, and rich it is — a work that foregrounds extra-subtle shifts in resonance and intonation.

personal back story [ skip this if u’re in a rush ]

I was first introduced to shade/gradient by Edgars Rubenis, around 2018. Feeling both estranged and moved by it, I quickly asked if we could try to analyze and recreate the piece together in SuperCollider. At the time, neither of us were familiar with the world of just intonation or rational tuning; and this piece turned out to be a perfect entry point for grasping the basics of that musical language/theory.1 But back then, we could only go as far as the LP booklet allowed us, which included the score for the viola part. Since then, I’ve had the unexpected privilege of taking part in the rehearsal / transmission processes of the piece between Cat and Elisabeth Smalt in 2024, as part of the Echonance Festival. This experience offered me a completely different perspective. Not only did I gain access to the full set of materials—including the SuperCollider patches for the electronics—but, more importantly, I witnessed the precious exchange of words between Cat and Elisabeth, the way we all groped around in the dark together, before slowly, slowly finding light.

On paper/score, the building blocks of the piece are relatively simple; but the moment you begin to engage with its realization, the incredible complexity of the work quickly reveals itself. And that, dear reader, will be our path of exploration: starting from the score, moving through the electronics, touching on the unwritten instructions around how the piece is sounded, and arriving, inevitably, at some ethereal concluding thoughts [cuz u kno i can’t help it]

primary colors (fundamentals / roots)

Here is the first page of Cat’s score. You won’t find traditional notes here—only color names, each corresponding to the fundamental of a specific harmonic series. Accompanying each color is an Arabic numeral (e.g., “red 1”), indicating its position within that harmonic series, a Hertz value (such as “30 Hz”), and a set of ratios. These ratios represent the intervals formed between each pair of colors/Hertz values. For example: the interval between 30 Hz and 32.5 Hz corresponds to the ratio 12/13, while the interval between 30 Hz and 35 Hz corresponds to 6/7, and so on.

This first page demonstrates an incredible ability to distill complex information to its bare essentials, all with a clear internal logic, a strong sense of structure and transparency (+ a charming handwriting). It also reflects a synaesthetic approach to sound. Whether or not you personally subscribe to this perspective, in Cat’s world, 30 Hz (and its harmonic relatives) is interchangeable with “red,” 32.5 Hz with “yellow,” 35 Hz with “green,” 37.1875 Hz with “cyan,” 39.375 Hz with “blue,” and 48.125 Hz with “magenta.” In that sense, blending these tones may truly be akin to mixing watercolors—yielding increasingly refined, complex, and rich. . . gradients.

A few additional/personal/extrapolative observations & speculations

All the Hertz values listed here fall below the threshold of human hearing. I love that. It suggests a kind of meta-music approach: a way of engaging with music, sound, and composition that extends beyond strictly human perception, perhaps even trusting the unfolding of the music, without the need for it to be fully heard.

Similarly, beginning the score with these extremely low fundamentals and the micro-differences between them (ranging from 2.5 Hz to 18.125 Hz) subliminally reveals a core intention of the piece: an uncompromising exploration of micro-intervallic/comma-related precision and tonal density.

If we zoom in on the ratios formed between these fundamentals, we can already identify different “limits” or harmonic flavors based on their prime factors: 2-limit (ratios involving the prime 2, such as 13/14), 3-limit (ratios involving the prime 3, such as 17/18), 7-limit [u get the idea], 11-limit, 13-lim and 17-lim.

In brief: quite an opening.

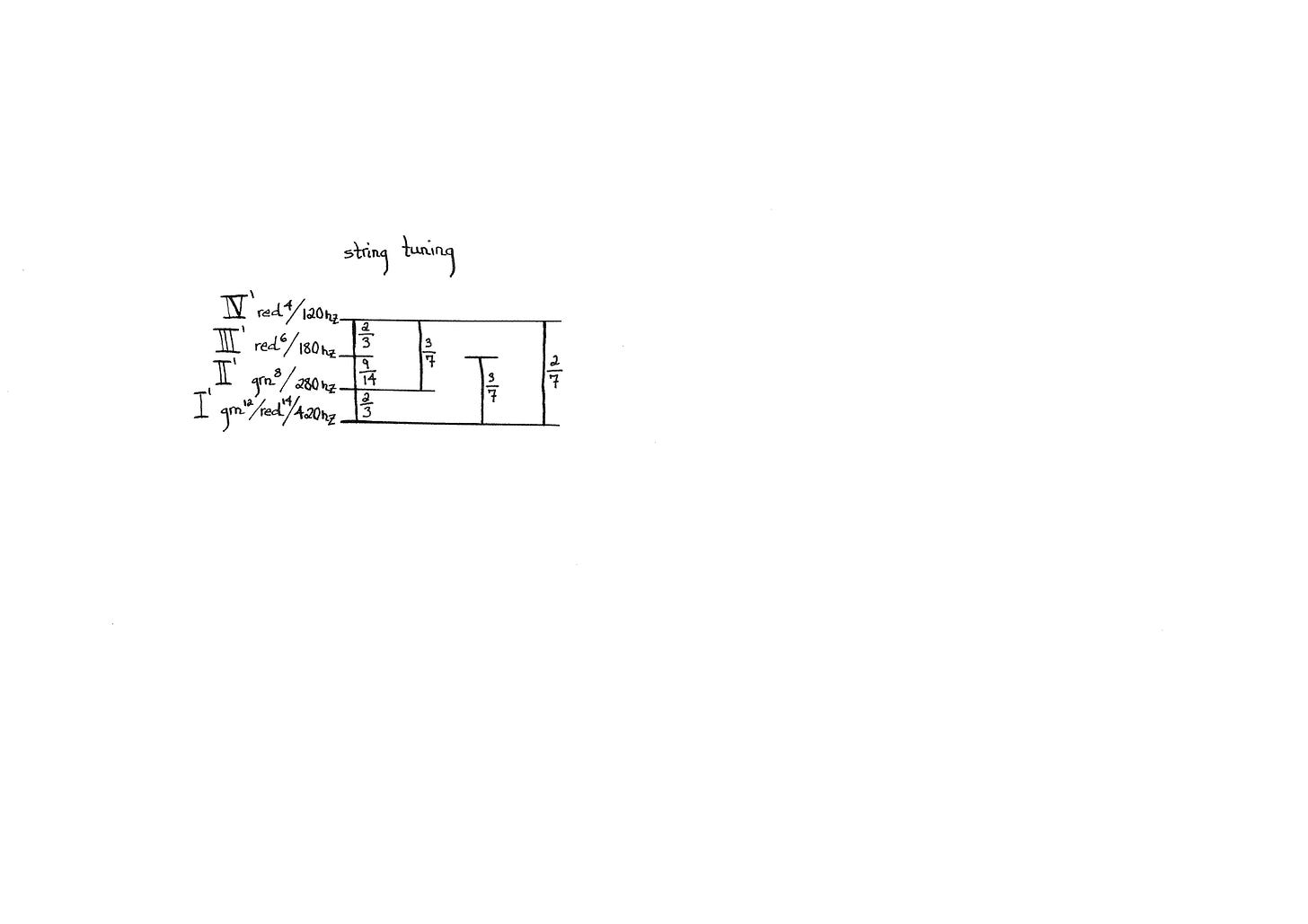

string tuning

The next page of the score presents the specific scordatura required for the piece, i.e. the tuning of each open string on the viola. Compared to page 1, page 2 feels like a breath of fresh air: the ratios between the strings are simple and relatable. Between string IV and III, the ratio is 2/3 (120 Hz to 180 Hz), followed by a septimal coloration between strings II and I (280 Hz to 420 Hz), themselves tuned a perfect fifth apart. The overall “colors” assigned to these four strings are also elemental: red and green.

Yet, after that initial moment of relaxation, a performer might quickly wonder [/panic] how to achieve the intervallic precision of page 1 with such a simple scordatura. And honestly, that’s exactly where the piece reveals itself as a mind-blowing exercise in tuning and listening.

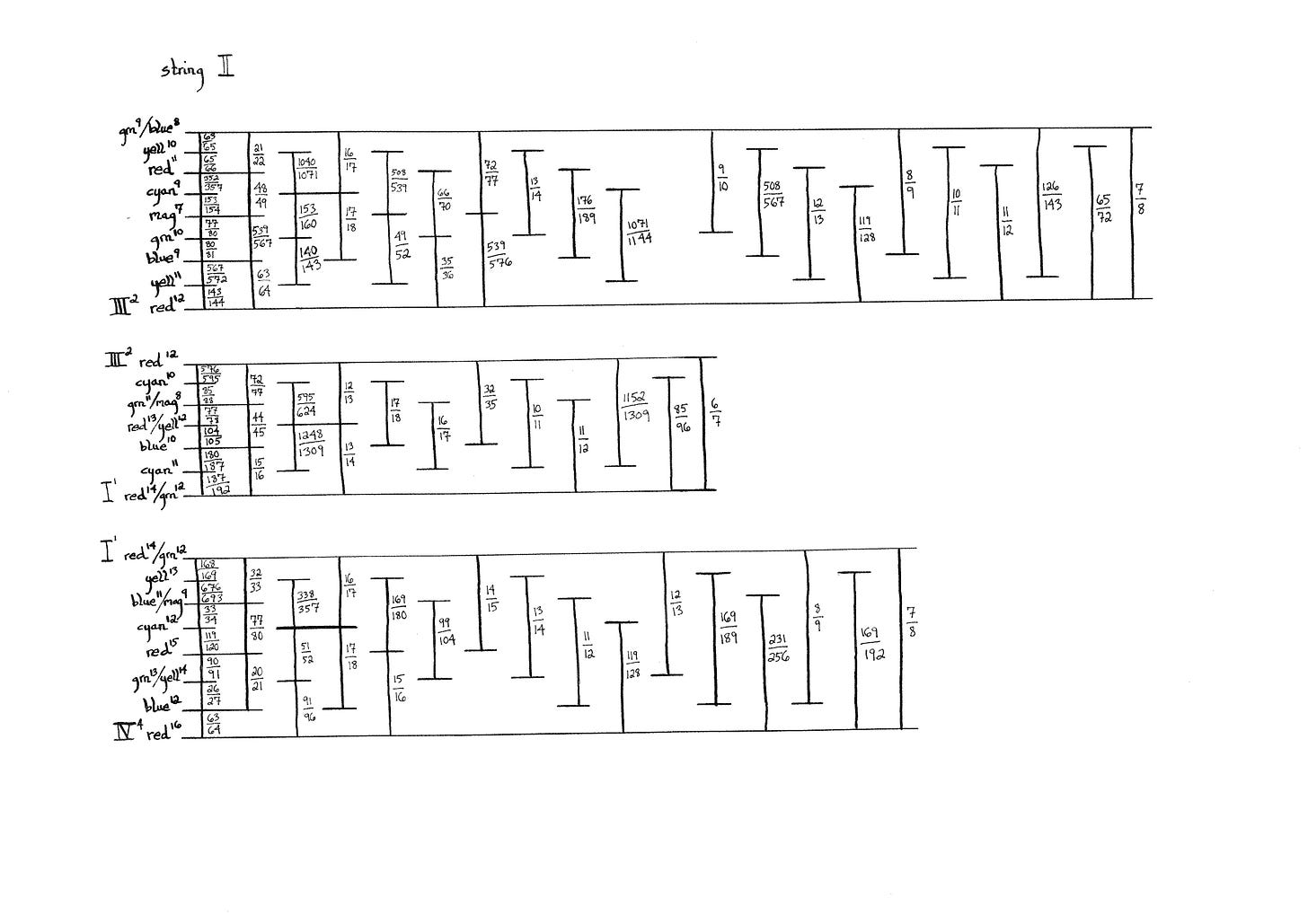

adding shades & gradients (secondary ratios / branches) : a systematic exercise of tuning, string per string

The next page of the score begins with a simple instruction: “low to high.” Each string is explored systematically, from the lowest (string IV) to the highest (string I), and within each string, from its lower tones to its higher ones. This page also provides an overview of the intervals to be explored on string IV, laid out one block after another:

A performer might begin by focusing on a “pool” of tones, first between the open string and 8/9, then between 8/9 and 7/8, and finally between 7/8 and 6/7 —zigzagging between these microintervals/commas and their associated colors.2 The delineation of interval zones serves as clever and effective landmarks within each string—both as a notational strategy and as a practical consideration for tunability and finger placement. In practice [more on this in a few §], the performer isn’t expected to rigidly explore every tone on a string from low to high. Rather, they actively choose which subdivisions to explore and which tones to activate, all while maintaining the overall directional movement from low to high.

The next page, focused on string III, begins at the endpoint of string IV (red 7 / grn 6) and continues with similar subdivisions of intervals (7/8, 6/7, 8/9), while also including potential connections to other strings—through harmonics, for example.

When we turn to page 3, dedicated to string II, we find the following interval map:

By introducing references to other strings—both open strings and harmonics—the score encourages the performer to play double stops, revealing new timbral colors. For example, string I (red 14 / grn 12) can be played as an open string simultaneously with a tone from the higher section of string II. Similarly, string III’s second harmonic may be paired with tones from the midsection of string II. Conversely, string IV’s fourth harmonic can be played in rotation with tones from the lower section of string II. [ nb: hope i’m getting this right, if not please lmk as my dyslexia makes it sometimes impossible for my brain to know what is low or high, right or left etc ]

electronics on Supercollider

The electronics were programmed on SuperCollider by Bryan Eubanks [ who, btw, also composes/performs excellent music]. More than just supporting the viola score, the electronics act as a kind of navigational map and backbone for the piece. They trace the same low-to-high trajectory as the score and strictly follow its pitch material. Crucially, mirroring the performer’s meandering through the score, they’re not fixed: the electronics unfold as probabilistic sequences of randomized tones, often overlapping but also leaving space for silence. Without revealing the entire SuperCollider code, I’ll share some key snippets here & there.

synthesis — formant oscillators

Throughout the piece, a single type of synthesis is used: formant oscillators that generate harmonics around a formant frequency, designed to emulate the resonant frequency bands of the human vocal tract. This connection is especially compelling given shade/gradient’s vocal part.

To keep it brief, the formant synths in shade/gradient have several key inputs:

a fundamental frequency, multiplied by a variable partial that changes over time.

a formant frequency, which is also based on the fundamental but multiplied by another variable.

a band pulse-width frequency in Hertz—essentially the same as the fundamental input—which controls the bandwidth of the formant.

This synths then pass through a bandpass filter whose resonance (quality factor, or RQ) changes linearly over time, from a narrow starting band (minimum Q) to a wider one (maximum Q). The synths are further shaped by an envelope with a short 0.1-second attack, a variable sustain, and a 0.1-second linear release, plus a bit of reverb and randomized panning. Boom.

macro perspective — synths routine

Formant synths are triggered randomly within a routine, each assigned a randomized fundamental frequency and sustained for a random duration, ± always exceeding the waiting time between triggers, ensuring these synths overlap.

For example, at the start of the piece, each synth is triggered roughly every 30 seconds, gradually accelerating to about every 13 seconds by the end of part 1 (the exploration of string IV). At the beginning of part 2 (string III), synths trigger at random intervals between 11 and 30 seconds before stabilizing around 13 seconds. Similar patterns apply to the following sections, with trigger intervals shrinking to between 1 and 7 seconds in part 4 (string 1).

Viewed statistically, the piece follows a broad arch: longer trigger intervals at the start, accelerating to shorter intervals toward the middle, and then lengthening again towards the conclusion. The durations each synth is sustained also follow a similar arch—starting longer, then shortening, then lengthening once more near the end.

It’s all beautifully & precisely crafted, giving the piece its distinctive and undeniable rhythm.

micro perspective — parametric detail of each synth

Another meticulous aspect of the piece lies in how each synth is carved. There are 26 synths in part 1/ StrIV, 32 in part 2/StrIII, 42 in part 3/StrIV, and 29 in part 4/StrI. Overall [each of these parameters would deserve a specific statistical analysis]:

The six fundamentals/colors (30 Hz, 32.5 Hz, 35 Hz, 37.1875 Hz, 39.375 Hz, and 48.125 Hz) appear in each section to varying degrees throughout the patch, mirroring the viola’s parts and their varying colors.

As mentioned before, these fundamentals are multiplied by a random partial, ranging between 8 and 16 and gradually increasing as the piece progresses.

The patch includes conditional amplitude adjustments: if the partial is below a certain threshold, the amplitude is louder; if it’s above another threshold, the amplitude is softer. This helps keeping higher tones at a soft amplitude level.

There are also randomized panning positions (among 9 potential positions).

A very clear linear progression occurs in the minimum resonance quality (RQ) of the bandwidth filter: this value smoothly increases over the piece, moving from low RQ ranges (between 0.025 and 0.1) up to higher ranges (between 11 and 19).

Since each synth’s parameters are manually defined, shade/gradient shows how a piece can be both probabilistic and meticulously shaped in its parametric detail.

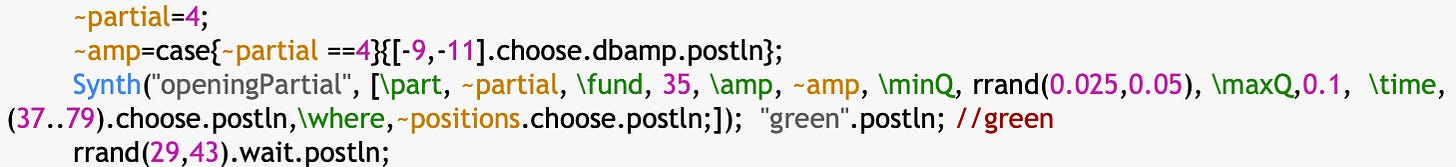

Example of a synth at the start of part 1/strIV: the partial (4) multiplies the fundamental (35 Hz), producing a tone at 140 Hz, belonging to the color green. This tone passes through a BP filter with an RQ ranging from 0.025 to 0.1. The synth sustains between 27 and 79 sec, while the next synth triggers randomly between 29 and 43 sec:

Example of a synth at the beginning of part 4/str I — notice the change of partial (chosen between 14,15 or 16), of minQ and maxQ (random number between 7 and 17), sustain time (between 5 and 43 sec), and wait time before the next synth (between 3 and 19 sec):

Example of at the end of part 4/str I — notice the change of partial (18), minQ and maxQ (randomized between 11 and 23), sustain time (between 2 and 30 sec), and wait time before the next synth (between 1 and 5 sec):

In effect, every aspect of the electronics mirrors the structural maps laid out on each page of the score for the performer. Some might argue that the programming could be more streamlined or synthetic—but in this case, I think the pointillistic, detailed approach is entirely justified. It is consistently crafter, rather than arbitrarily manufactured, and serves the piece’s precision and clarity. And, crucially, it reflects a clear intention to break habits, to resist the lure of passive droning, an intention just as present in the electronic layer as in the performance practice.

ALRIGHT—still with me? good moment to take a little break before diving into the final stretch of our analysis.

aural instructions: detailing the interdependent relationship between string(s), voice and electronics

Here’s an essential but unwritten aspect of the piece: the performer is invited to select and play the different tones not only on the viola, but also with their voice—sparingly, minimally, and within the limits of their vocal range. This requires developing a literal physical intimacy with the intervals, locating them on the viola’s body and one’s vocal chords, sustaining them all steadily, without vibrato.

More precisely, here are some of the unwritten performance principles I’ve gathered from listening to the piece and rehearsing it with Cat and Elisabeth:

Cat’s use of her voice and vowel shaping in the recording is masterful—subtly mirroring the behavior of the formant oscillators and bandpass filters.

There is a delicate interplay between with the durations of a) sustained notes & bowing of the viola b) silence c) a breath. Each tone’s entry and exit is never ‘round’: they emerge and fade as distinct layers. [ btw, the ending of the piece is phenomenal, precisely because of its simplicity & complete absence of climax ]

That same simplicity defines the beginning: the electronics remain a quiet, steady guide; the focus rests entirely on one “voice”= one string. Double stops and vocal tones are introduced slowly, each on their own terms. [for ex, in Cat’s recording, i believe the first double stop enters at 5’50”, with much restraint]

Later in the piece, even amidst a dense and complex mixture of tones, moments of unison emerge—brief pockets of light.

One of the most beautiful instructions given by Cat to Elisabeth when rehearsing the piece was the following: the piece is like “meandering through a forest where colors fuse or contrast. Sometimes it’s dark, sometimes light cuts through. Sometimes, you stop to look at one tree, then return to the forest as a whole.” As a performer, you focus on a single interval that draws you in, then shift back to the full texture of the piece. You move between the score and listening, tracking tones on the viola, in your voice, and in the electronics. You recall a tone, return to it, or leave it behind. You propose something new, then let it fall into silence, never holding on too tightly to any mixture produced. And this, my friend, is no less than a spectacular deed.

multiple configurations & ‘site-specific’ aspect of the piece

The piece unfolds through the interdependence that arises from the probabilistic layering of its elements (viola, voice, and electronics). The result depends on the ever-shifting configurations the piece makes possible:

< ‘no sound’ (i.e. the sound of the room) >

< ‘no sound’ + electronics (none/one/several tones) >

< ‘no sound’ + electronics + string (none/single/double) >

< ‘no sound’+ electronics+ string + voice >

Once again, the core challenge of the piece lies in cycling through and balancing these layers—allowing blocks of density to emerge, linger, and dissolve. It’s a navigation between density & clarity, silence & sound, a single pitch or unison & complex clusters, the muddiness of certain intervals & the clarity of simpler ones.

One last interesting aspect: the electronics in shade/gradient are systematically rearranged depending on the site/space, the time and length of the performance, and the speaker setup available. =The piece is conceived in relation to its environment. For example, when I was in charge of the electronics during the Echonance Festival, it was a delicate and fascinating task to find the right level. The goal was not only to balance the viola, voice, and electronics so that none would overpower the others, but also to preserve the original intensity and density of the piece while projecting it in a larger hall—very different from the intimacy of the recording.

conclusion: pieces are enriched by their transmission to others

As mentioned before, Cat has transmitted her piece to another viola player, Elisabeth Smalt, for the first time. Passing on a piece you’ve been the only one playing for years is a courageous act. It requires a great capacity to let go of your attachment to the work [ ur little bébé] and allow it to continue blossoming, with or without you. It’s not easy, but ultimately, it’s what we are all fortunate and meant to do.

Analyzing pieces—whether they are others’ works or your own, in academic or informal ways—feels to me like a continuation of this transmission process. I cannot express how grateful I have been to study pieces with friends. Perhaps this is one of my love languages: immersing myself in listening and dissecting a piece with others, or discovering it through the eyes, ears, and care of someone else. In a simple, fundamental way, these analysis remind us how we all long to understand and to be understood—in our fleeting or lasting curiosities, confusions, questions, & in what we create, perceive, conceptualize, or simply experience at a given moment in life.

All this to say: maybe this analysis has touched some of you, maybe my longing to understand and be understood has found a meeting place with yours. Consider this as a very preliminary, bird view analysis, as shade/gradient would deserve much, much more. [for ex: JI graphs with all the ratios in the piece, statistical analysis of their unfolding in the piece (score / SC patch), aspects of performance, eeeetc]

Abruptly cutting here, Cat-style:

à la chaine-pro,

Lucie (your pépé Jean-Claude)

i won’t get into the basics of JI / rational intonation, but if you need resources & such, lmk.

i imagine each performer may develop a different way of reading the score, practicing it and relate to these microintervals/commas, either purely through listening (with or without electronics), remembering a physical distance between them, etc.