'assisting' others

reflecting on ± one year of assisting other composers

Dear reader,

I hope the end of the year is treating you well, and, that, well, your year ends with treats. Yesterday was my birthday (yay) and I felt like reminiscing about one of the best gifts I’ve received over the last year: assisting other composers at Orgelpark, Amsterdam (NL).

Since its 2024 edition, I have had the great pleasure of working together with Claudio F Baroni for the Echonance Festival at Orgelpark. Although I am officially a producer/coordinator, I have another invisible ‘hat’ as a technical assistant. In brief, I help commissioned or invited composers during the (re)creation of their pieces, and in particular, if they wish to use Orgelpark’s two computer-driven or so-called ‘hyperorgans’. It is an invisible ‘hat’ as we don’t make publicity around our multifaceted roles with Claudio, but also for another fundamental reason. When assisting other composers, the assistant is/becomes invisible if they do a good job — to achieve a complete transparency or seamless workflow between the composers and the music they envision. So, if all goes well, my work begins with assisting these composers and ends with receding completely in the background, solely witnessing (with wonder) their compositional process.

So, let me humbly open the door to these ‘behind the scenes’ glimpses of what assisting other people in composing looks like from my perspective. I did not anticipate working with composers I admire so much, but here I am. To the expense of sharing technical details, I will try to keep it short & informal/simple —we’re here to relax after all.

[2024] Remembering Clarence Barlow — developing a later intimacy

The first process I’d like to share is a metaphorical kind of assistance — one where I adapted the piece Für Simon-Jonassohn Stein by Clarence Barlow, a few months after his passing. At that time, we all felt the urge to pay tribute to his life and work. Originally, Für Simon-Jonassohn Stein was written in 2012 for the Saint-Peters Church’s hyperorgan in Cologne, and later on rewritten for Dutch Ensemble Modelo62. We thought playing the organ version of the piece at Orgelpark would be a great idea.

In all honesty, I didn’t know Für Simon-Jonassohn Stein too well and did not anticipate how much work adapting it for Orgelpark’s two hyperorgans (Sauer and Utopa) would entail. So this task had a very big speculative dimension, reinforced by the fact that I had never met Clarence before his passing.

As I started engaging in this project, it became clear that although Clarence had extensively written about his compositional methods for the piece, there was little available documentation to be found on its realization per se. For instance, I had the MIDI files of the piece but were not sure how he played them on the organ at the Saint-Peters Church, i.e. which registers he used or if he used other effects like changes in air pressure and so on.

So, I just began to feel my way along: analyzing the original MIDI files extensively, listening to the two versions of the piece for organ and ensemble, translating the MIDI messages thanks to a comprehensive SuperCollider patch sending OSC messages straight to Orgelpark’s organs along with changes in registrations (all this in collaboration with Andrea Vogrig), and of course, choosing the right registrations for this new, 2024 version of the piece. I made several versions of the piece for the two hyperorgans at Orgelpark, following different logics: staying as close as possible to the original solo organ version, combining the organ and ensemble versions, imagining other versions following the overall structure of the piece or simply experiments I wanted to try — and mostly, imagining what would have been the most musically fulfilling (and fun) version for Clarence.

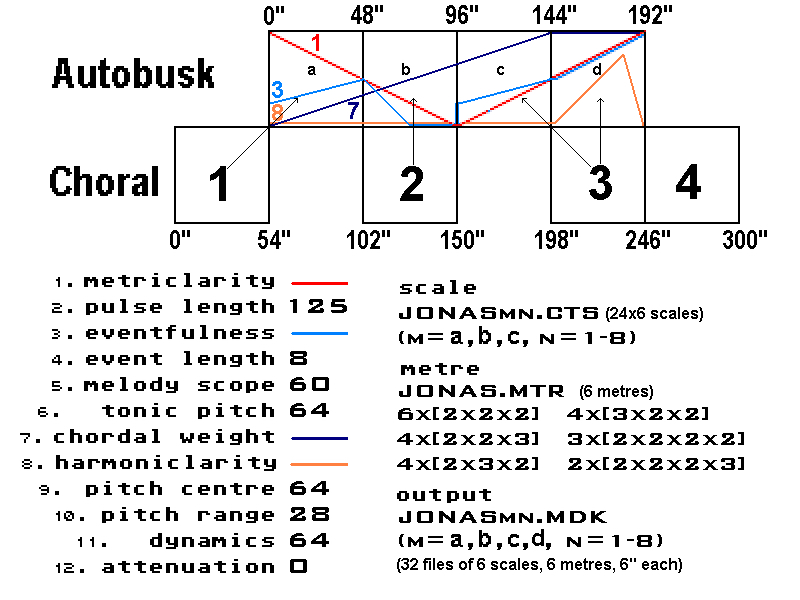

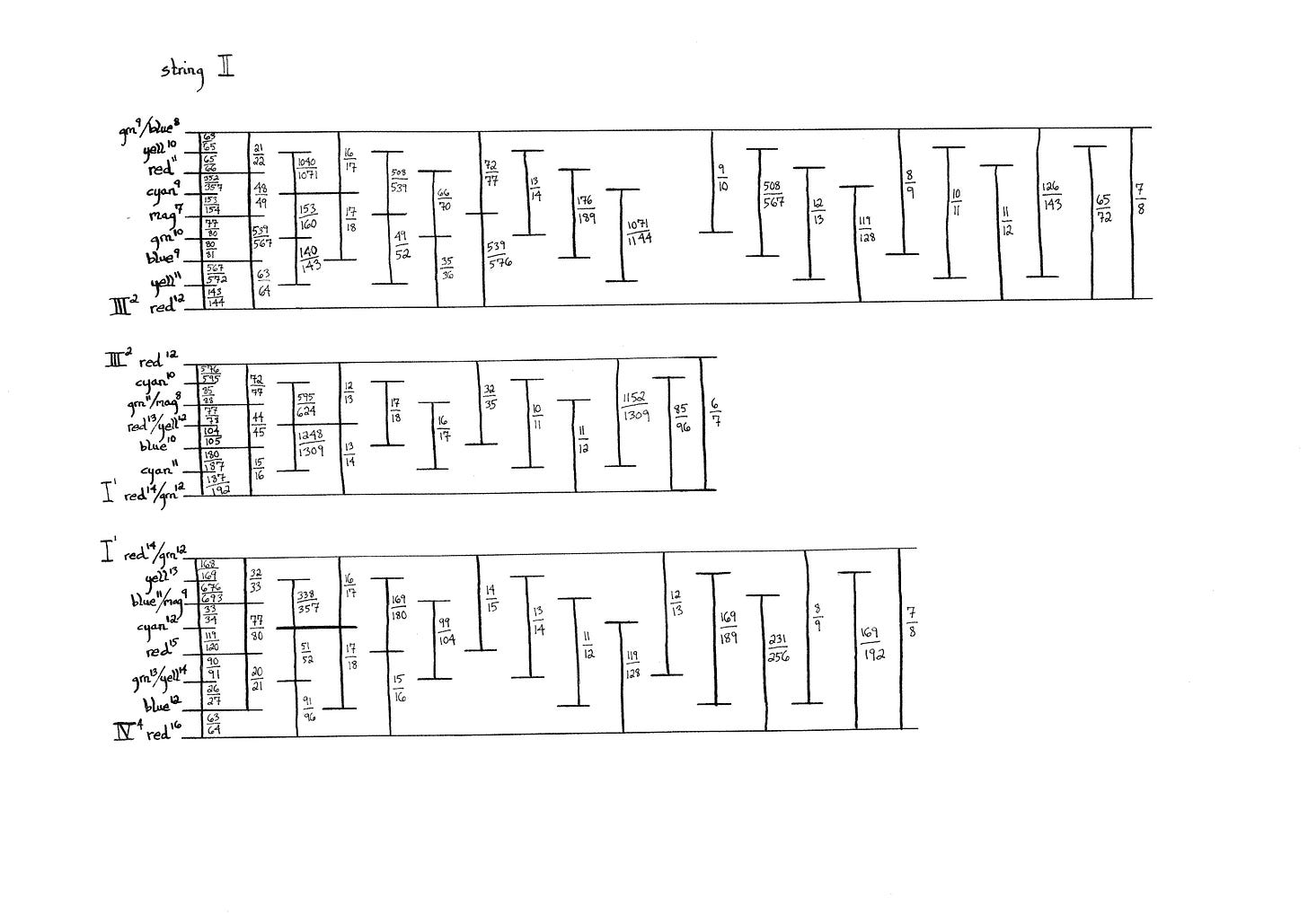

My main finding was that the piece’s macro structure was mainly defined by Clarence’s choice of ‘orchestration’, which was a rather simple, linear sequence of accumulation of registers, from soft to more imposing ones (if not slightly grotesque). This sequence was somehow superimposed on the conceptual, algorithmic ideas beneath the piece, with a great talent, musicianship and sense of humor. In the 2024 version of the piece, the simpler my choices of registrations on the Utopa and Sauer, the better. Similar to how Clarence orchestrated the ensemble version of the piece, I mapped each organ to each of the customized algorithmic program used by Clarence in the piece. The Utopa rendered the MIDI files related to the ‘Autobusk’ improvisations, and the Sauer organ played the MIDI files generated following the ‘Chorale synthesis’ algorithm. And at the end of the piece, both organs played the last Chorale section of the piece. Coming to this simple conclusion was perhaps laborious but enlightening.

A personal take away from this experience was that there is much responsibility involved in caring for and perpetuating a composer’s musical lineage. And taking on this responsibility is rewarding. Throughout this process, I got to know ‘a piece’ very intimately, but, most importantly, I have found a way to thank Clarence for his work and its influence in my own musical path. It might have been a bit too late, but maybe we kind of met at last, somewhere between memento mori & memento vivere.

[2024] Bridging Catherine Lamb and Elisabeth Smalt — witnessing transmission

Still for the 2024 Edition of Echonance at Orgelpark, a second assistance experience I was involved with was related to the transmission of Catherine Lamb’s shade/gradient to the viola player Elisabeth Smalt. The piece consists of 3 parts: one for viola, one for voice and one for sine tones. The first two parts are derived from the piece’s score — which is kind of a proposition of path(s) where the performer goes through rationally tuned intervals — and the electronic part is is probabilistically generated on a standalone SuperCollider patch, originally programmed by Bryan Eubanks.

Before this project, I had an intimate connection to the piece very well. In 2018-9, my friend Edgars Rubenis (who I will have the pleasure to introduce in an upcoming post) and I had already analyzed its score and reprogrammed all its ratios on SuperCollider. To me, the exercise was a first decisive entrance door to rational intonation and composition in general. A few years later, I had the great pleasure to meet Catherine during a residency and then in Berlin while I was living there in 2022-3. I’m especially thankful for the meetings she had generously organized at hers with other young composers like myself, where we had some collective listening sessions together, brought our scores, discussed all kinds of things — music making, tuning, art, life in general. Those meetings were highlights for our group of mostly solitary, perhaps a bit lost yet lovely weirdos.

Getting back on track: I was especially touched to help her and Elisabeth in any capacity to bring shade/gradient to Orgelpark in 2024. This was not any kind of performance, but a an actual transmission, from one composer/viola player to another. Until then, Cat had been the only performer of the piece so, Elisabeth was (again) feeling responsible for receiving this piece— and so was I.

After a first discussion with Cat, Elisabeth and I began dissecting the score, going through the different ratios present in the score, discovering the rigorous and wide kind of freedom of choices of pitches involved in the piece — and thus the incredible mastery required to perform it. The piece is like embracing and enhancing a complex palette of colors of intervals — and accepting to get completely lost (/ found) during the process. In Cat’s words, performing the piece is akin to a walk in a forest, staring at the trunks of one trees for a while, becoming aware at the vastness of the forest later, staring at the sun’s rays piecing through the trees’ leaves. And in the music itself, one may hear pockets of light resulting from the emergence of a rationally tuned intervals between bowed strings, the voice, and sine tones. [I would gladly write another post on this piece — thoughts?]

Elisabeth had already worked with just intonation system, but with a different notation. So we mostly spent some time going through each ratio and Cat’s ingenious approach of assigning colors to prime numbers and their resulting intervals. I also prepared some SuperCollider patches for Elisabeth to practice each section of the piece so that she would be as autonomous as possible, and feel comfortable using this technology without needing to know anything about SuperCollider.

Our first and only rehearsal with Cat and Elisabeth in Berlin was a privileged moment. I remember a quiet, focused, slow and intimate atmosphere, an overall dedication, an unusual care— and the softness of our interactions. Maybe we were all walking on eggshells at times (in the best sense possible), experiencing the vulnerability involved with this transmission process as it began to unfold under our eyes and ears.

Cat wasn’t able to be there during the concert at Echonance — so her complete trust with our work with Elisabeth (voice/viola) and myself (electronics) was touching and empowering. Elisabeth and I had to find ways to bring the intimacy of the rehearsal we had found with Cat, to Orgelpark’s concert hall — and bring audience members in ‘the forest’. Elisabeth impeccable presence during the concert was inspiring; and I believe we both let the piece spoke through during the concert.

A take away from this experience. It is quite beautiful for me to retrospectively observe a multifaceted transmission diffused patiently over many years, many people, many places. In some sense, the piece and its philosophy were passed on from a distance from Cat to Edgars, from Edgars to me, from Cat to our group of young composers, from Cat to Elisabeth and I, from me to Elisabeth, from Elisabeth to audience members, and back to Cat. Who ‘assisted’ who and when is no longer clear nor relevant — we got all lost and found in the same interdependent music forest.

/////

Let’s now move on to other experiences assisting the making of pieces to be presented in a few months in Amsterdam. As the works are still in progress, I won’t share as much as the previous ones but hope these previews will make you feel inclined to come join the Echonance Festival in February 2025 at Orgelpark.

[2025] Playing with Arnold Dreyblatt — the fruitfulness of (seeming) detours

The first commissioned composer for Echonance 2025 is Arnold Dreyblatt, who will present his new piece Descendants — Music for Four Pipe Organs in One Space.

When meeting online for the first time and discussing possible options for his piece and if/how I could be of help to him, Arnold explained he usually works very much on spot, finding out about the piece by interacting with the instruments, and perhaps an overall ‘situation’ (my interpretation), rather than by working ‘abstractly’ or planning in advance all kinds of schemes and procedures. To a certain degree, I’m kind of the opposite when composing my own music so I was slightly worried our differences of composing methodologies would prevent me from being truly helpful.

Arnold’s initial idea was to adapt a recent piece he had written for a hyperorgan in the Auenkirche in Berlin, for the two hyperorgans at Orgelpark. The piece was derived from the ‘Dreyblatt tuning system’, a rationally tuned scale based on the harmonic series where -3, -5, -7 and -11 limits are emphasized. The piece being written in MIDI, I was expecting a similar process than the one I had gone through with Clarence Barlow’s piece. Things did not go according to plan.

At first, Arnold, Claudio and I spent a lot of time figuring out if Ableton Live or Logic would be more efficient to Arnold to control the two organs at Orgelpark. Eventually, we found a way that was relatively satisfactory to Arnold on Logic, but working on the computer for this piece was somehow exhausting for all of us and not particularly pleasant. What was pleasant though was the extensive lunch breaks we had during the day, where Arnold was sharing a great amount of incredibly funny stories: his life in NYC, the many different jobs he had back then, his self-taught musicianship — interspersed with rather rather unconventional music lessons, like Chinese oboe lessons with Dewey Redman, the way he built different instruments fitting (or not) his tuning systems, his memories of his dear friend Phill Niblock, his life in Berlin since the late 80s. Arnold was reminding us something very essential here: making jokes, relaxing while composing is not trivial but very much essential and most likely beneficial to the music that is being made.

The next morning Arnold and I met at Orgelpark and this time, things were getting more serious and concrete. As I began to look into the mapping between Arnold’s session on Logic and the hyperorgans console, Arnold started to test another organ, the late Middle-ages replica organ Van Straten. He then came downstairs and asked me to play a number of pitches on this organ, sustaining them and changing their octaves to get as many combinations as possible, while he would do the same with different pitches on the Utopa organ. While playing together, I was hoping Arnold would hear the same as I was: this felt like a piece, and a very beautiful one. At some point, Arnold asked me to stop playing, and nonchalantly said we now just needed to rehearse what we just did, and that this would be the piece. The relief, joy and overall playfulness that emerged from that conclusion were palpable. In the meantime, Claudio had just arrived at Orgelpark, and happily joined the process. The three of us went through all the different organs of Orgelpark, testing which pitches were approximating pitches of the ‘Dreyblatt tuning system’. In the end, 4 of these organs were containing some of the pitches. Arnold decided he would play on the Utopa, Claudio on (his favorite) the Verschueren , I would play on the Van Straten, and Reinier van Houdt on the cabinet organ, renamed by Arnold ‘the Little one’.

What amazed me throughout this assisting process was to see that nothing had been lost from the time spent pondering if/how to use a computer in the piece or just laughing together. Arnold is not only generous with funny stories, but also his music and the joy of performing it. Last but not least, it is obvious that Arnold’s consistency and life-long experience with tuning were underlying and diffused throughout his time composing at Orgelpark. To me, his musicianship is a mixture of an expertise with tuning systems and the ‘tunability’ of instruments, as much as a presence/availability for the unexpected and ‘attunement’ to the situation.

[2025] SuperColliding for Chiyoko Szlavnics — soft meticulousness in action

Next to Arnold, the 2025 edition of the Echonance Festival will also feature a new piece for organs and ensemble by Chiyoko Szlavnics, Concurrences: Circles of Light & Solar Winds.

Similarly to Catherine Lamb, Chiyoko Szlavnics had been/is one of my music heroes for almost a decade. I not only relate to the austere, radical beauty of her music, but also the genealogical/cultural scission present in her first and last names. Needless to say, meeting her and providing some technical assistance for her was a big deal to me.

During our first online meeting, I was immediately impressed by Chiyoko’s strength and intelligence, her structural thinking and articulate technical questions. In brief, she was as über cool as I had imagined her to be. At the same time, the mystery around what/how she would compose remained (and still remains) complete.

Differently from my work with Arnold, my task with Chiyoko had to do with preparing an open field of possibilities yet easily workable programming environment. It was about anticipating what could be needed in a SuperCollider patch for Chiyoko to compose for Orgelpark’s two hyperorgans i.e.: sending OSC messages for notes and registers, ramps to control the air pressure of the pipes and any other desired effects available at Orgelpark: tremolos, pulses, etc. [I’m thankful to Michael Winter for thinking along and helping me find an elegant way of programming these patches.]

When Chiyoko came to Orgelpark, she had already prepared some Excel sheets to manipulate strings very effectively and write each line of the SuperCollider patch in a very efficient way. It was striking to me to see how quickly very autonomous she was when writing the piece on SuperCollider, although she hadn’t used this program before. Her technical adaptability was truly humbling. It was as if she had created her own path in this open programming field, and was now ready to embark alone in her music journey. Therefore, the rest of the process remained completely hers, and again, shrouded in mystery.

Importantly though, Claudio I had the privilege to hear glimpses of the upcoming pieces and were amazed by her way of intuiting and mastering timbral explorations with the two organs. Her process felt to me like a quasi-immediate synthesis of rational intuitions — when (in my own experience) this process of synthesis tends to usually take months, weeks, if not years. Chiyoko’s mastery of timbres is also very evocative, calling to the listener’s mind numerous extra-musical images in a poetic assemblage. Being able to do all this with computer generated processes is an achievement. When technology doesn’t affect in the least one’s composer’s style but reinforce it, letting it shine even more brightly, this usually speaks for this composer’s craft. It certainly did speak for Chiyoko’s artistry, as well as the depth and intensity of her focus.

I am glad to say there is nothing else I can share about Chiyoko’s compositional process and upcoming compositions. I cannot, cannot wait to find out about the integrality of her piece, including its ensemble part, in February, almost like any other audience member.

A few last thoughts

Working with/for other composers is kind of an indescribable, simultaneous process of zooming out and zooming in — like witnessing from above the way they work, while potentially providing an assistance that could be as precise, minute as possible. It is also about developing an openness to the different modalities of composing.

I’d like to specifically note how special and precious it was for me to sense the solidarity among female composers/musicians when working together. Probably for the first time in my life, I felt how profoundly related our music and life experiences were — without needing to even mention it. I also see how essential it is to develop spaces for us to share safe, non-judgemental, non-’trying-to-prove-something’ but simple/neutral (if not positive) spaces around using technologies such as SuperCollider.

Last but not least, I’m amazed to have received trust (and patience) beyond measure and would like to extend my gratitude (by order of appearance) to Claudio, Andrea, Cat, Elisabeth, Arnold, Michael and Chiyoko. Also, you still have a chance to join the Echonance Festival at Orgelpark, Amsterdam in February and listen to Arnold and Chiyoko’s works on the 7th and 8th of February 2025.

super best,

Lucie

ps: let me know if any of you would be interested in ready a more thorough analysis on Catherine Lamb’s shade/gradient in the future