intersecting (1)

Cenk Ergün / Celare (2015)

Dear reader, salut beauté,

Thank you for being back here, and welcome to the weird zone again.

So. Here we are, our hearts shattered — aren’t they. As they keep breaking open, it feels like we’re all in some collective gestation phase, layering slowness with urgency, actively, continuously deciding and discovering how (ir)responsible we are with the life growing within us, around us, how far we can (must) grow alongside it. I wish us all the best kind of luck and the quiet determination to keep growing.

In the meantime, allow me to lift your spirits, even just a little [/ make you regress ].

Today’s post is a special one, for at least 2 reasons:

It marks my very first two-part post series. I might start spreading some posts out in the future, to go a little deeper into certain topics [ + sneak in my repertoire of stupid jokes ] [ pouet pouet ]. Ironically, though, posts won’t get any shorter.

This specific series was partly sparked by the dis ce que platform—which still blows my mind. The composer we’ll explore today found my earlier posts and reached out before I even had the chance to ask. He kindly agreed to have his music featured here, along with some extras I’ll be sharing with you, dear reader. So, this little branching-out moment is very touching — and a good reason to keep writing non-sense, because sometimes that’s where virtuous circles begins.

Allez Jean-Claude, on désenfle ses chevilles, on pose sa brouette et son arrosoir, on prend son courage à deux mains et sa plus belle plume. ô rage, ô désespoir,

ô manifesting love, positive cashflow & successful business announcements

you now have the possibility to buy me coffee here: https://coff.ee/disceque

i’m currently gathering ideas to organize reading/support sessions with you on themes dear to dis ce que= music-making + (mostly) everything surrounding it. if any of you are curious and/or want to contribute, put your hands up

encountering Cenk’s music (while writing mine)

This story begins with the string quartet I’m currently writing for Quatuor Bozzini.

That project was, and still is, hmmm a little confronting. I’ve always walked this thin, precarious line where my non-conventional musical path and beginner’s mind are either my greatest strength or my downfall. I’m not quite sure which side I’ll land on this time. Let’s just say: this piece has brought up every part of music-making I find difficult: notation, communicating with performers, and other technical things. And honestly, I’m not sure I’ll find the fix for it all. Continuing with my gestation/parenting metaphor: no matter the food fed, the lullabies sung, the diapers endlessly changed, the tenderness nested in between, this baby of a piece keeps needing to be soothed. And yeah, that’s it, you know. Sometimes, writing a piece feels like sticking with a screaming baby (or teenager) and learning to love the process anyway. [ reminder: u are the bébé ] [ oh i kno we’re all cringing at this point ] [ the discomfort of softness ]

Three extraordinary things have already come out of this project: a) basking in the hot-ness of Montréalais people, tabernacle b) truly, truly, remarkable conversations about music-making [ hugs to David, Nirantar, Julia, and Niko ] c) Zosha Di Castri’s suggestion that I listen to Cenk Ergün’s work, which I followed upon returning from my residency last June. That’s when I first encountered his work—and, in a way, silently befriended him through his music, before knowing anything about him as a person. I say befriended because his music gave me a profound sense of relief and renewed momentum; the kind of inspiring, gently destabilizing support you only receive from a friend. His music seemed to offer a kind of mirroring I had long been searching for: a precise, almost uncanny form of shared acknowledgement/reconciliation with things/inner experiences I had been trying to articulate in my own work, without yet being able to name them. One of those was the near-absence, and the resulting need for reinvention, of a contemporary music language grounded in non-Western performance, modal systems, and tuning practices.

So. Let’s shall, shall we? As usual, we’ll start with a look at Cenk’s bio and a brief introduction to his music—plus a few personal thoughts and sprinkles along the way.

Cenk Ergün’s bio / music

Cenk [pronounced “Jenk”] Ergün is a Turkish composer and improviser based in NYC, whose work spans it all: acoustic and electronic music, live performance, collaborations with musicians, choreographers, filmmakers, and sound installations.

Born in 1978 in İzmit and raised in Istanbul, he grew up surrounded by Western classical music but non only. As a teenager, he picked up classical guitar while immersing himself in metal, rock, and contemporary music—and became fluent in English along the way. Clearly brilliant, he was accepted to Eastman School of Music at 17, where his work—already minimalist, dry, and provocative, earned him the self-described title of “black sheep.” He then went to Mills College for his Master’s at 21, where he studied with Alvin Curran, Fred Frith, and Pauline Oliveros.

Between 2002-2003, Cenk went through a period of what I call positive disintegration — literally getting lost, walking around California, and eventually returning to Istanbul. These non-linear meanderings, so characteristic and precious to gifted minds, coincided with the lead-up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the growing prevalence of racism toward people of Middle Eastern descent, like himself. Still, in 2004, Cenk (courageously) returned to the U.S., where he began teaching audio engineering. Fast forward to 2010: he started a PhD in composition at Princeton, where he later taught. More recently, after a few years spent in Berlin, Cenk is now based in NYC again, continuing to teach and compose, while maintaining ties with the Berlin scene and collaborators like those in the Harmonic Space Orchestra.

In his own words, Cenk is “interested in building near-static sound fields made up of repeated patterns, sustained tones, and what can be called islands of sound: brief sound events surrounded by silence.” To me, his aesthetic signature could be described as an interplay between two distinct yet interconnected modes: on one hand, sparse, kaleidoscopic forms (his “islands of sound”) where precision in tuning is subtly veiled beneath soft, delicate timbral textures and slow mutations; on the other, more transparent patterns and uniform timbres, where tuning emerges more assertively and clearly. This alternation doesn’t feel like a division, but rather a process of individuation: a weaving together of complementary opposites in pursuit of balance. Throughout it all, a certain quality of silence remains ever-present, permeating his music with a sense of spaciousness and quiet intensity.

I’ve chosen two different string quartets by Cenk, written roughly ten years apart. Today, we’ll focus on the first: Celare. As always, I don’t claim to offer an exhaustive/academic analysis, rather an introduction shaped by my own subjective lens that might spark your curiosity to dive deeper. [ + in all honesty, the depth of my analytical/writing capacity was inversely proportional to my overwhelming bias and goosebump reaction to the pieces ]. Alright dear coco, on y go.

Celare (2014-5)

Illustrative of Cenk’s two-sided signature, Celare is the twin piece of Sonare. Both pieces were written for the JACK Quartet during 2014-5 and are Cenk’s earliest works written in alternate tuning systems. If Sonare is a dense, buzzing, microtonal piece composed through rhythm patterns using Max/MSP1, Celare is a much sparser, quieter piece. Listen here [ +link with score available here ]

Celare’s reference sonorities & tuning

Originally, Celare’s sonorities were informed by early string quartet music, in particular Sonata a quattro No. 4 by Scarlatti.

Cenk explained that while experimenting with frequency ratios and reframing early European musical references through the lens of just intonation, he "stumbled upon" melodic fragments reminiscent of Turkish modes. 2 [ofc, this kind of stumbling is never entirely coincidental ]. This meeting point between early European and Turkish music, shaped by the influence of the American school of rational intonation, forms the foundation of Celare's scale and tuning system.

The piece’s clarity and precision of tone are achieved by focusing throughout on a single 12-tone scale, mostly colored by septimal (7-lim) intervals, with touches of 13-lim and 11-lim harmonics — echoing the finely calibrated microtonal systems found in Turkish tuning. There’s also a single nod to a -5-limit interval. More precisely, the scale is based on A (0 ct) and includes a 3-lim tetratonic anchor: the pivot tones C, D, G, and A. From this foundation, additional tones branch out, derived from or approximating the harmonic series of:

D (7th harmonic = C -33 cents),

G (7th = F -35 cents, 11th = C +47 cents, 13th = E -63 cents),

C (5th = E -20 / -31 cents, 7th = B♭ -37 cents, 13th = A -65 cents).

My general sense is that the micro-intervallic differences in tuning (particularly between tones like C, E, and A) function not only in harmonic fusion when combined as chords, but also quite vividly in sequence, that is, in melodic “isolation.” Moreover, as we’ll see, the tonalities in Celare appear with varying degrees of clarity or transparency. This depends on two key factors:

a) the timbral, dynamic, and instrumentation context in which they’re presented, and

b) the simplicity or complexity of the tone combinations from which they emerge.

In this way, tuning in the piece is not just an abstract compositional tool, but is intimately tied to, and continually reshaped by, its sonic and contextual unfolding.

a brief chronological analysis of Celare

Celare unfolds in a beautifully semi-symmetrical and fluid form, enhanced by its unmeasured temporal framework.

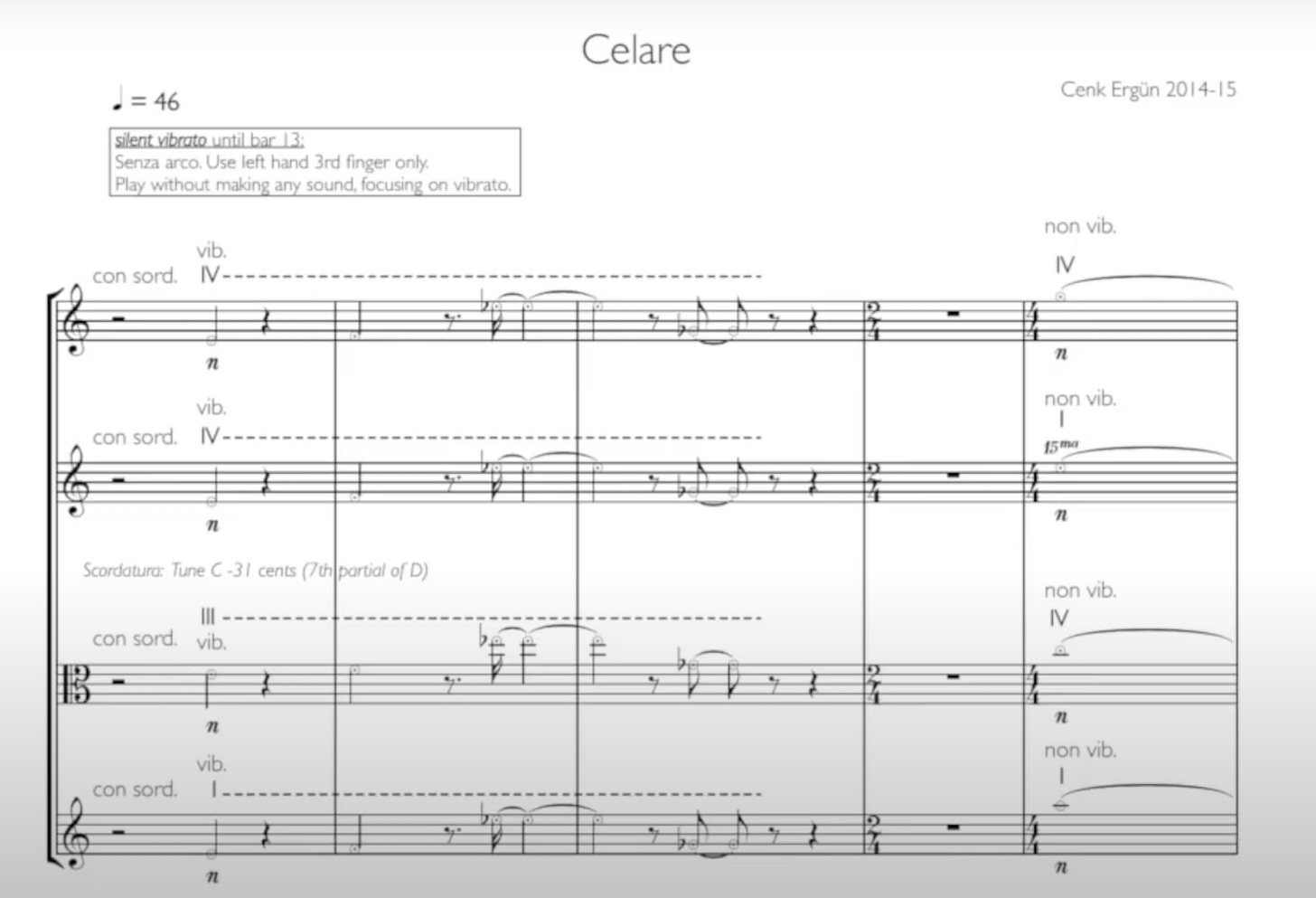

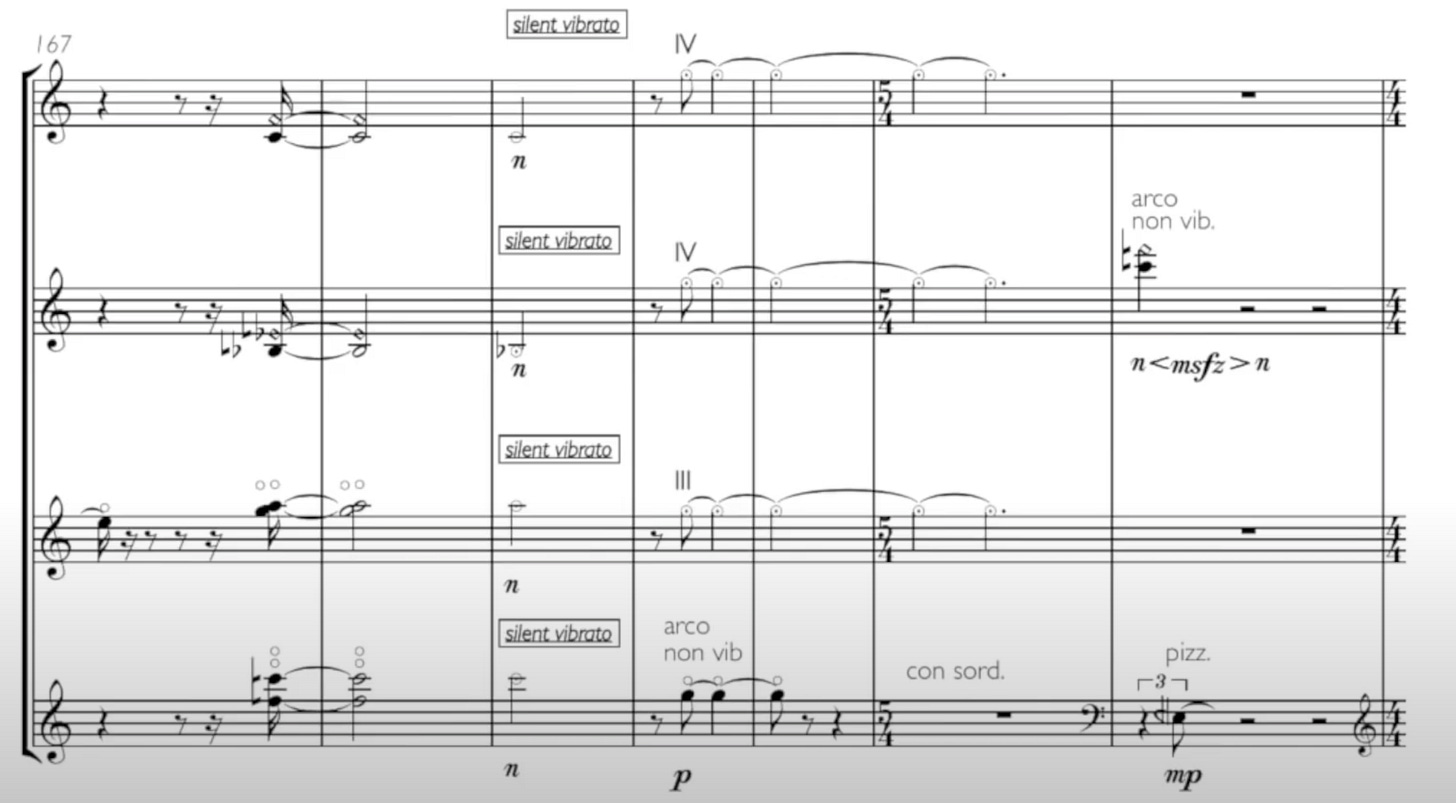

[0’00”-1’00”] part 1 / introduction — lively silence

The first minute of the piece features precisely tuned notes played silently by the quartet using mutes and alternating between vibrato and non-vibrato.

Jay Campbell, cellist of the JACK Quartet, described these sounds as “all vibrating and you’re hearing nothing. Then, all of a sudden, they stop. You’re focused in a different way.”3 Beyond their perceptual effects on performers’ and listeners’ attention,4 these silent notes also evoke a kind of silencing—as if the tones had been gently muted yet continued to resist in their liveliness. In other words, the silent tones don’t feel neutral; they are charged, like carrying a persistent presence and meaning.

Last but not least, the pitch material beneath these silent notes is revisited throughout the piece, emerging with varying degrees of audibility, timbral lightness, and softness.

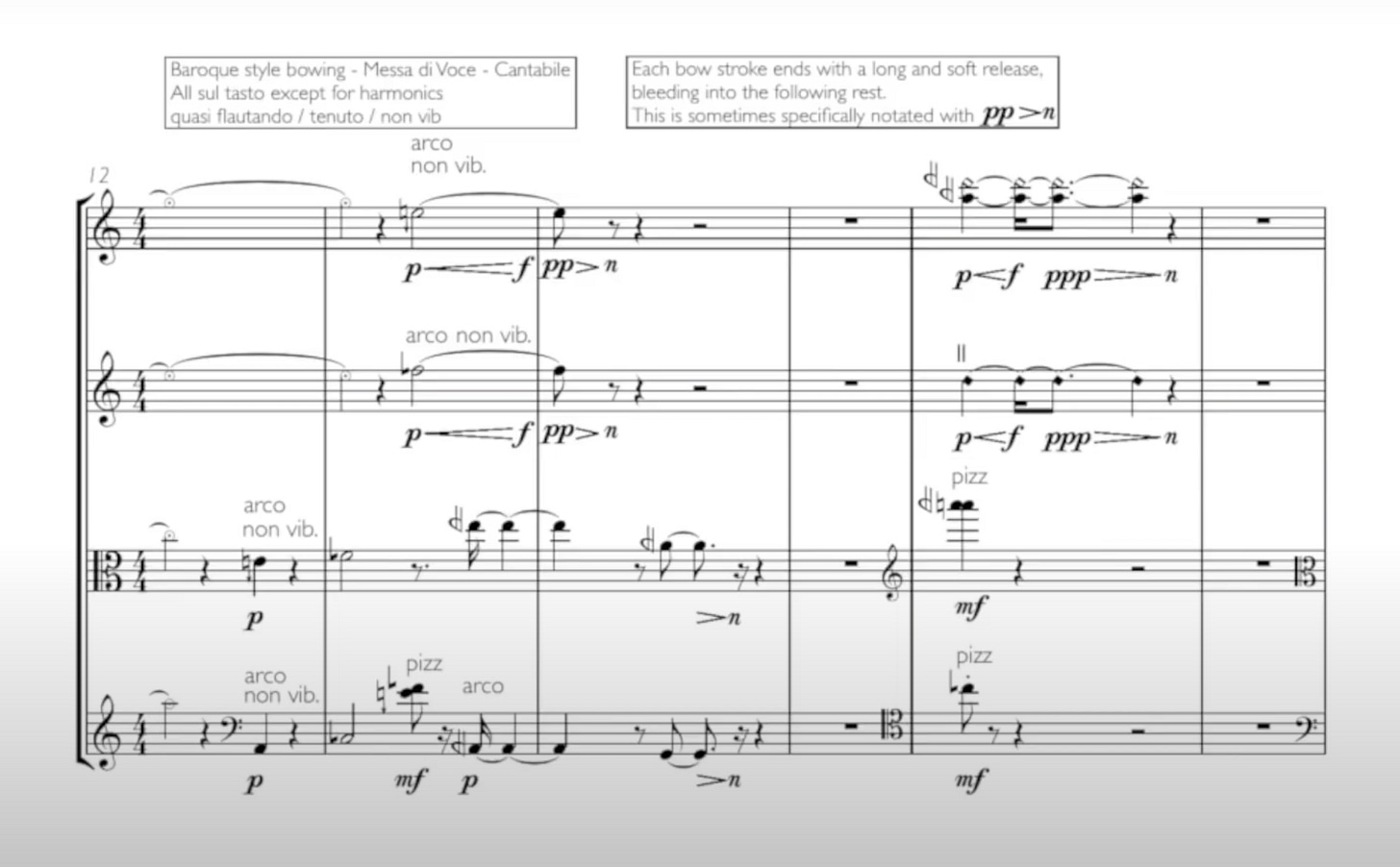

[1’30”-6’00”] part 2 — sparse Messa di Voce

The following section5 features short, widely spaced non-vibrato tones and chords that resemble fragmented melodies revolving around E, D, F, A, C, and G, played with messa di voce, the Baroque technique of fading each bowed note in and out. The meticulous dynamics and articulations, combined with two-note motives (such as the M6/m3 between D and F -35 cents, octaves between A and A/A -65 cents, D, and F), create descending melodic fragments that generate a pendulum-like movement. Chords emerge and dissolve within silences, interspersed with softly plucked notes, primarily in the cello part.

As a listener, one experiences fragmentation both horizontally, through these broken melodic events unfolding over time, and vertically, as the melodic material travels across different voices in the quartet. Amid this fragmentation, “pivot notes” can be discerned, guiding subtle modulations within the fragments.

Although the main chords and building blocks of this section are fundamentally consonant—based primarily on P5/P4 —dissonance emerges on two distinct levels:

micro level: when two pitches are doubled with slight accidental deviations. This mostly occurs around Es (E–20ct, E–63ct, F–35ct), As (A 0ct, A –65ct), and Cs (C –33ct, C +47ct).

macro level: when chords are spread across a wider pitch range and combined with brighter, more ethereal timbres—mainly harmonics and flautando.

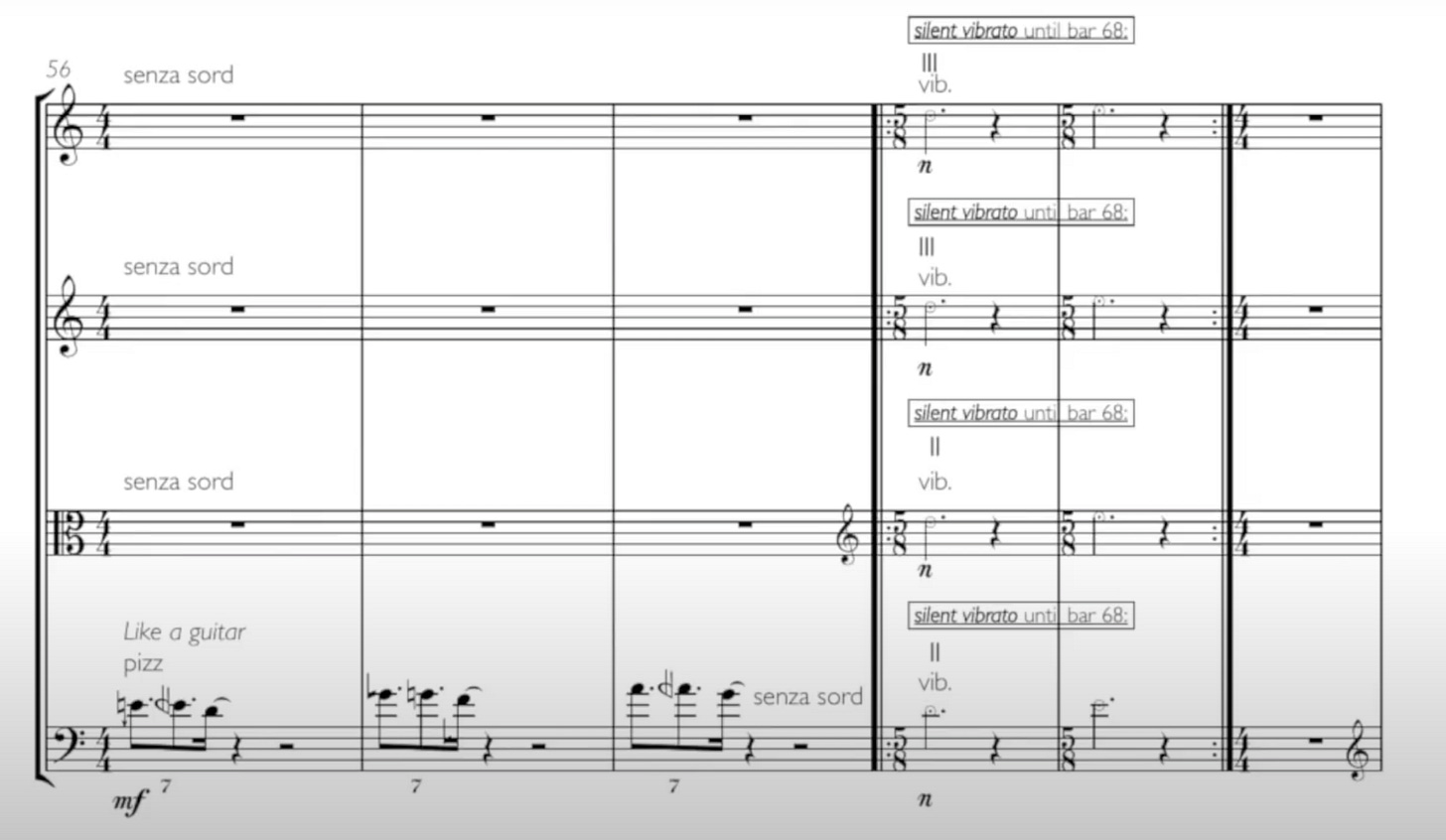

Towards the end of the section, the pizz notes on the cello gradually moves to the forefront, culminating in a solo passage played in a “guitar-like” style. This solo features three descending scales of three notes each, marked by very precise micro-intervallic differences. You’ve guessed it by now: these plucked scales evoke “relics of [Turkish] monophonic music”, reminiscent of ajnas — the building blocks of maqam.

This section ends with silent notes as in the piece’s introduction — only this time, with different pitches/octaves and played without mutes [ every detail counts ]

[6’00” - 7’45”] part 4 — introducing sustained, naive-like in-between chords and scales

This part expands on the previous material, evolving into more continuous, block-like chords. What can I say. This section is lovely [lol, not even trying to be objective]. Cenk introduces what feel like “naive” chords that shift into ajnas-like ascending and descending scales of 3, 4, or 5 notes, repeated several times. I say “naive” because Cenk dares to present this minimal material with such delicate care, working with an overall timbre that is slightly muffled, quiet, and very restrained.

[ Cenk described Celare as having “a moment in the piece which I think of as Turkish music with the piano pedal down.” could this be the one? i luv it. moving on ]

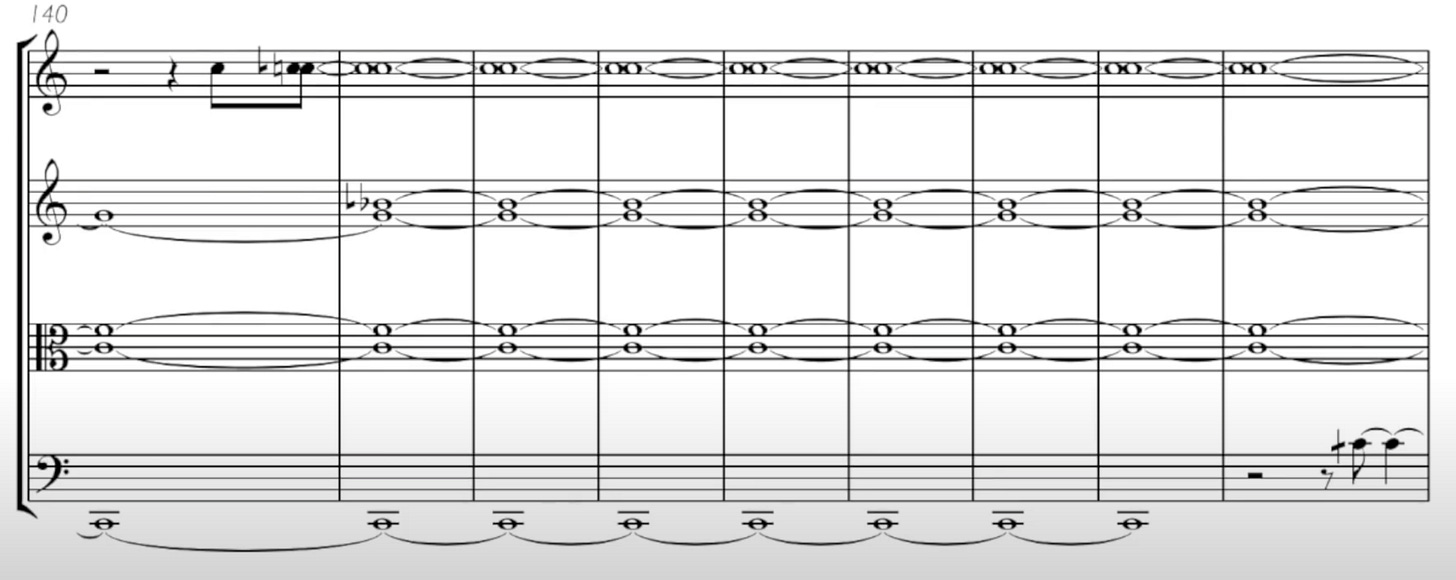

[7’45” - 14’45”] part 5 — sustained chord progression

This section begins by freezing one descending scale from the previous material and reframing some of the ajnas into a (no longer “naive”) succession of slightly louder, denser, and more compact sustained chords in a lower pitch register. Revisiting the piece’s tuning through these longer durations is especially effective and moving.

Without going into the details of its [ stunning ] chord progressions, here are some notable aspects of this section:

The chords begin as very compact structures built from adjacent tones within a perfect fifth or less and including micro-intervallic differences between pitches. As the section develops, these chords are harmonically spread out, while still preserving those subtle microtonal deviations.

The anchor pitches of the progression are C and E (in all their tonal “shades”), with touches of G, F (treated almost as a “sub-color” of E), and B♭ (similarly acting as a “sub-color” of C).

A central feature is the emphasized septimal color, particularly highlighted by the cello tuning its C string down by 31 cents. This allows for a moment of “mixtured unison” around C, where violins and cello sound C natural, C –33 cents, and C +47 cents simultaneously. When the cello eventually retunes its C string back to C natural, the contrast enhances the perceptibility of the septimal color and its accompanying beating patterns, making them shine even more vividly. In Cenk’s words, “seemingly static on the surface, there is a kinetic energy in each chord”.

Much could be said about the way the instruments enter and exit, sometimes creating a kind of spectral masking between them, at other times emphasizing the subliminal presence of ajnas and their ascending/descending trajectories woven into sustained tones. For example, in m. 140–141, we hear the two violins play a three-note descending ajna, which they then sustain—melody and harmony intertwining and amplifying one another.

Even as the material becomes denser and more resonant, the piece never reaches a climax. The music remains contained and restrained, which, paradoxically, makes it all the more moving.

[14’45” - 16’30”] part 6 — (incredibly) soft return to sparse textures

As we are now fullbodily attuned to the pitch colors of the piece, the next section introduces clearer, block-like chords built from the same material, but now gradually transposed into higher and higher octaves. These chords are interspersed with single notes (or very light chords) that pass delicately among the four instruments, and with general pauses — silences in which the previous section seems to continue resonating internally.

Timbrally, this section acts as a synthesis of everything that came before. It traces a kind of envolée, both in pitch and its increasingly delicate disappearance of sound. It begins with ordinario bowing, shifts progressively toward higher and higher harmonics, and finally dissolves into silently fingered notes.

This is pure gold, pure gold, dear reader.

Toward the end of the section, the cello quietly reintroduces a single pizzicato and the small two-note melodic motive from the opening —this time descending from D5 to a lower D4 (or E4 -20ct), preparing for Celare’s epilogue.

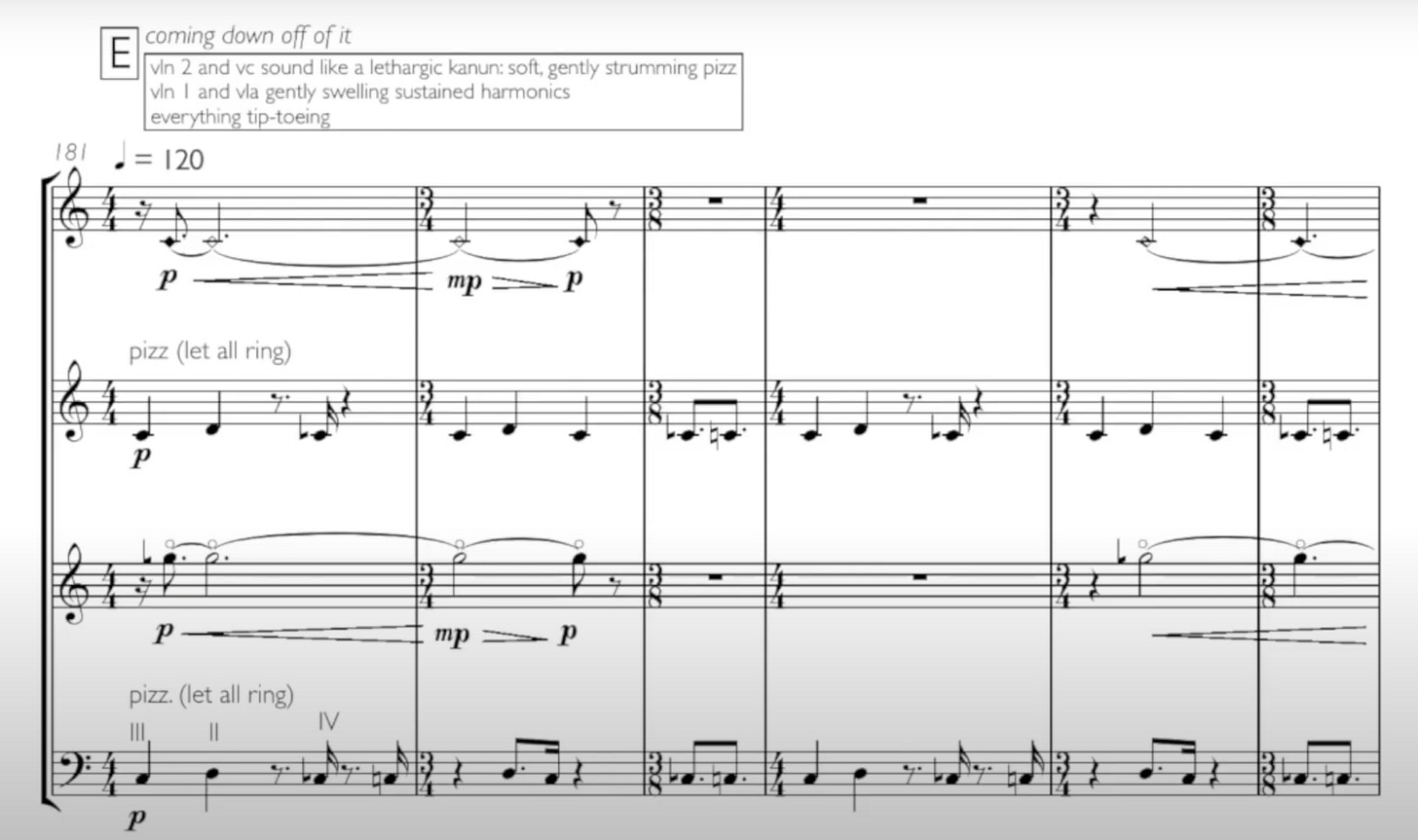

[16’30”- 17’00”] part 7 / epilogue-”coda” — further unveiling of Kanun references

Far from being anecdotal, the final 30 seconds of the piece feel especially decisive. In this closing section, a heterophonic texture emerges: a single melodic line shared between violin II and the cello, always revolving around and ascending from C (-33 and/or nat) and D, while violin I and viola sustain C natural and G -27ct.

These final bars brings the non-Western musical references in the piece more clearly to the surface. The score explicitly cites the kanun as a reference, reflected not only in the pizzicato timbres of the violin II and cello, but also in the rhythmic and pitch “geography” of the melodies. I also hear the reintroduction of mutes as a subtle timbral nod to Arabic violins (keman). Cenk also described this “strange coda” as “informed by the cyclic rhythmic modes (usul) in traditional Turkish music. Without knowing why, I wanted to end the piece with this seemingly irrelevant gesture.”

Much like the silent vibratos in the opening, this return of the mutes weaves a full-circle metaphor. These more audible references to Turkish music feel offered à demi-mots — half-spoken, or as the score itself notes, “everything tip-toeing” — which, to me, makes them all the more profound & moving.

phenomenology of silence and fragmentation in the piece

Silence and fragmentation strike differently in Cenk’s music.

For him, silence functions as a “fundamental tool for shaping our experience of time”. In other words, it is self-reflective. At first glance, one might draw a parallel with Cage or the Wandelweiser composers, who also foreground silences in their work. But in Cenk’s case, are not “dissociative,” dreamy, or open-ended but feel sharp, saturated, imprinted with an unspoken personal significance. There’s a tension in them, as if they are holding something back. Some listeners might miss this subtle quality; but for those who feel it, it cuts deep.

My sense is that this quality of silence, and the fragmentation that accompanies it in Cenk’s music, reflects a process of inner and geographical dislocation and of reintegration. And the silences in Celare felt so poignant to me as they mirrored not only Cenk’s trajectory but also my own. It is as if the piece’s compositional language spoke directly to the psychic and geographic landscapes I’ve inhabited, consciously or subconsciously, both in life and music. In simple terms, the piece made me feel understood to the core. How cool is that.

[ = i mean: it’s astonishing. i can’t get over what music can do. if you allow me to put my rational woo woo hat for a sec: there’s a point where music operates (for listeners and composers alike) as a permeable membrane between the inner & outer, like a threshold where the personal and collective unconscious merge. music can speak of/to these places. that’s how deep, radical it can be ]

beware of what discreet pioneering may look like today

Now, the same goes with tuning/ pitch stuff. I believe the most innovative approaches to tuning are integrative — reconciling the self, exposing an inner journey of finding (or remembering) oneself through music. In that sense, the soft resurgence of maqam tonalities in Cenk’s music isn’t nostalgic, but a mutable, continually evolving intersection of histories unfolding within. As Cenk noted in an interview:

When I find things like [relics of Turkish music], I’m reminded of the intersections and exchanges among people, music, and ideas over millennia — in this case […] around the Mediterranean. This is a cultural heritage I identify with and find in my music, so I’m personally motivated to think in these terms.

In general, the reappearance of modal monophony/heterophony in today’s contemporary music raises parallel questions. Many of us — myself included — are stubbornly returning to tuning complexity and melodic simplicity as a way to recentre our work and express voices shaped by, but not limited to, non-Western musical lineages. If this material may sound “too simple” or “too homogeneous” to some, it holds meaning for us. Modal monophony/heterophony becomes shared ground for those who’ve listened across traditions and are now re-integrating non-Western traces within themselves. It’s as if our simple melodic lines whisper: “hear, there’s more to it.”

So, writing this kind of music doesn’t reflect a lack of technique. Quite the opposite — it signals the emergence of a refined and speculative technique that merges contemporary compositional codes/tools with aurally transmitted practices. When we draw from music that is a) emotionally close to us, b) only partially inherited, and c) transmitted outside of written archives, we enter something inherently experimental. This process is not auto-ethnographic (which would demand traceable sources, archives, and genealogies and seek to achieve an accurate reconstruction of some sort). But it’s closer to auto-archeology: a speculative, open-ended, sometimes subversive monologue, resulting in music that can sound disorienting or ambiguous. But often, it carries a message like: “maybe this piece was shaped by this, maybe by that, who knows — I do, and I don’t. And that’s exactly what I wish to share. ”

I want to highlight how much courage this kind of music-writing takes. It reflects resistance to being fully shaped by dominant musical voices, but more importantly, a desire to grow. That kind of inner growth isn’t defensive — it’s defenceless.

////

Okééé. That was that dear reader. I hope parts of the blabla made sense [& if not, please let me know — i’m also here for feedback & dialogue] . I’ll meet you with post no. 2 in August, where I’ll be thrilled to share some precious insights into one of Cenk’s most recent pieces, which, honestly, is ze bomb. I’m deeply grateful to Cenk for his trust. Until then, I’ll leave you with another beautiful vocal work:

monophonish-ly yours, but never voiceless

Lucie

/////// for more please read/ listen to

15 question: Cenk Ergun About Alternative Tuning Systems

Cello peace, an early piece from 2002

Sonare unfolds through repetitions of fast, loud, dissonant patterns, at times evoking the sound world of a swarm of wasps.

In addition, here is Cenk’s perspective on these silences: “These moments of silent playing are intended to magnify the visual grace of string players in action without any distraction from sound. Vibrato helps this cause, and perhaps at the same time pays a silent homage to so much other music that I love which uses it. It is interesting to observe how, during performances of Celare, silent notes without vibrato appear to be quieter than those with vibrato.”

nb: this refined section especially deserves a more thorough analysis